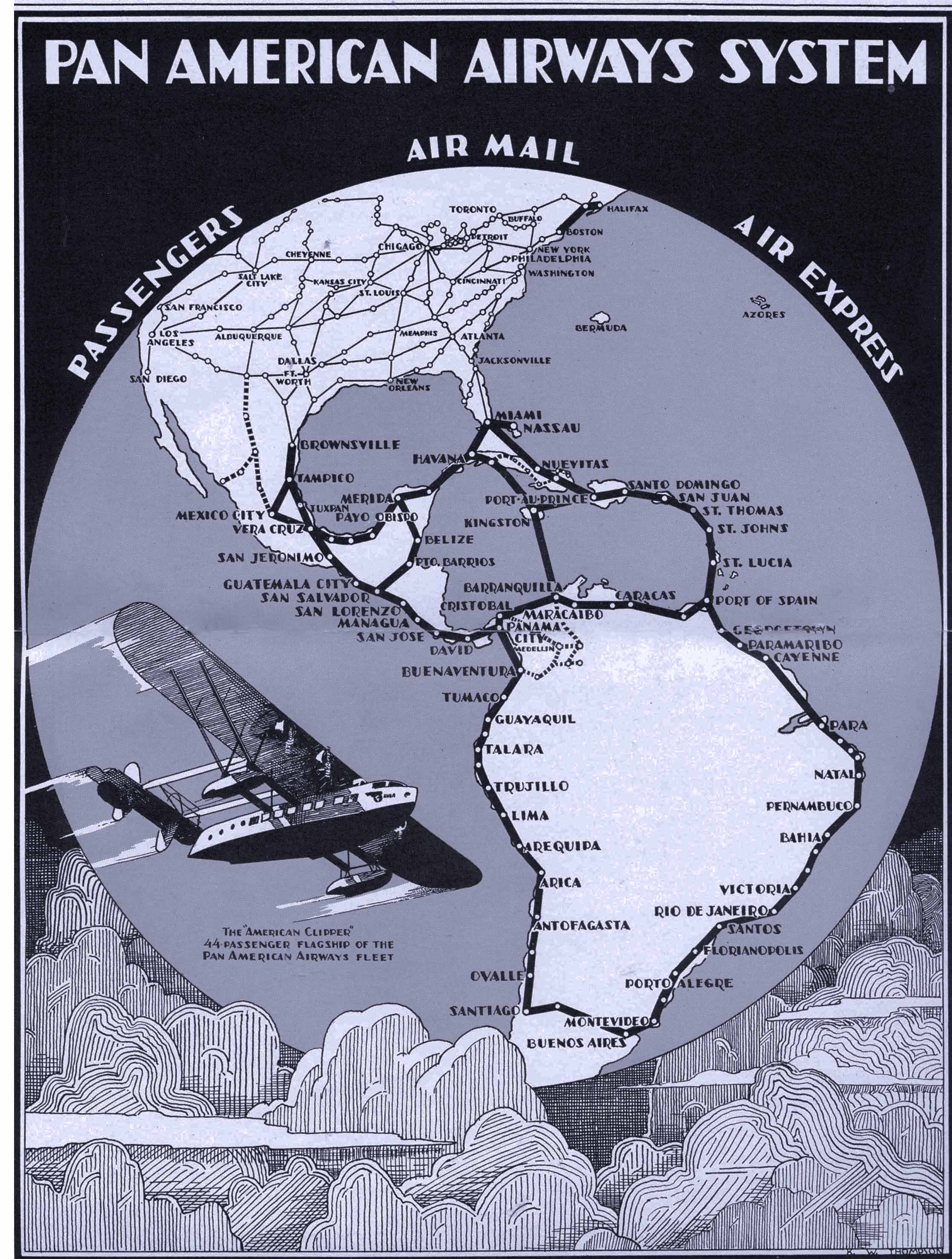

PAN AM

1932

EXCERPTS FROM "90 YEARS AGO 1932"

PAN AM EXPLORED ROUTES AND VENTURED INTO NEW TERRITORY. HERE ARE STORIES OF THE PEOPLE AND PLACES IN THOSE EARLY YEARS, DURING THE GREAT DEPRESSION, BY DR. ERiC HOBSON.

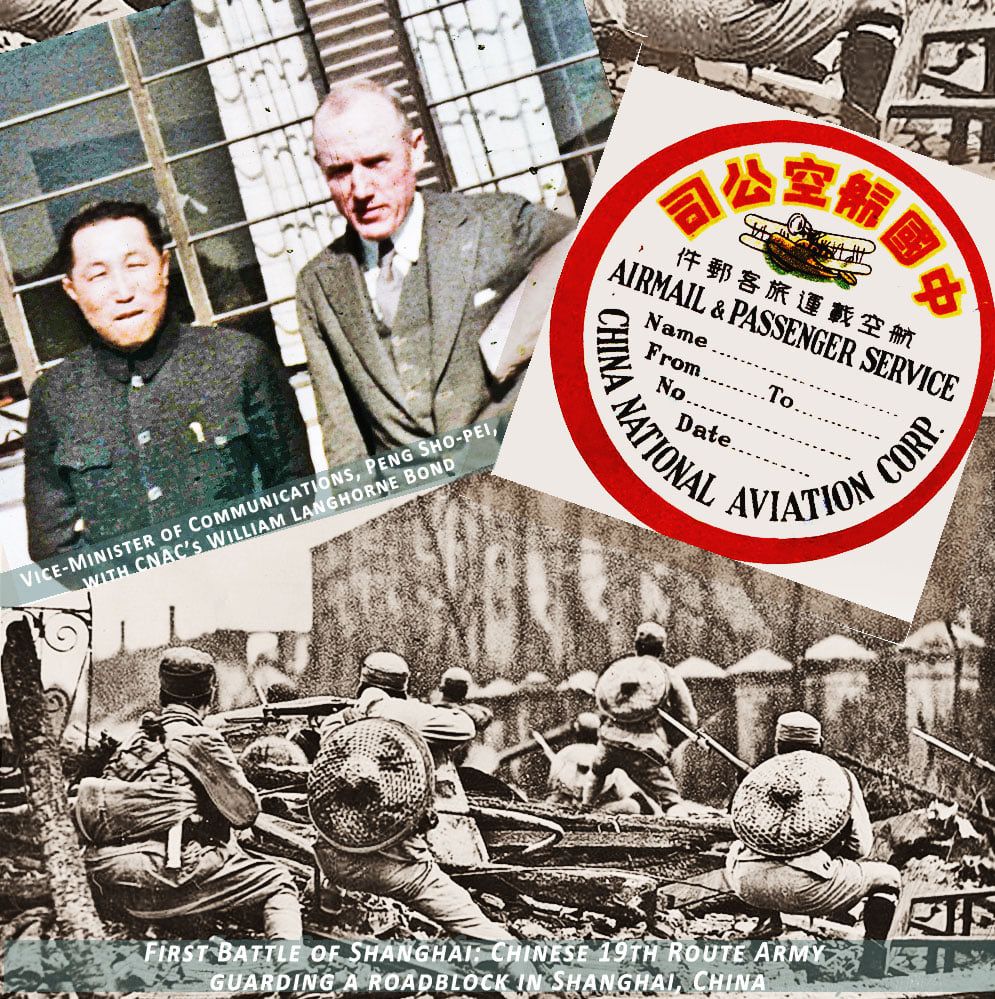

"Bond on the Bund"

January 28, 1932

SHANGHAI — William Langhorne Bond, Manager, China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), awoke seconds after midnight as Japanese airplanes began bombing Shanghai to open a coordinated attack on China’s most important city. The dawn’s view was grizzly: street warfare enveloped the city with more than 150,000 combatants involved by the week’s end.

Regardless, Bond had CNAC flying its regular schedule into China’s heartland within the week, and, by doing so, confirmed that air-services had rewritten warfare models: aircraft can leapfrog ground clashes and break military sieges.

The “Shanghai Incident” lasted five months (25,000+ persons died: 10,000 Chinese and Japanese soldiers; 15-20,000 Chinese civilians), served as an opening salvo to World War II, and as the first indiscriminate aerial bombing of civilians.

Despite the turbulent and often dangerous operational conditions, Pan American Airways bought 45% of CNAC fourteen months later (April 1, 1933) and Bond ran the airline until PAA sold out in 1949 following the fall of the Chinese Nationalist government.

For most of that that decade and a half Bond and CNAC did not fly in peaceful airspace. That dicey experience, however, provided Pan Am a laboratory from which emerged invaluable lessons that PAA put to use throughout World War II and beyond.

For more on the “Shanghai Incident,” William Langhorne Bond, C.N.A.C, and PAA:

Gregory Crouch, “China’s Wings” (Bantam, 2012).

Eric Hobson, Mission to China, Parts 1-4.

Photo:

Clockwise from top, 1. Film frame of CNAC William Langhorne Bond with Peng Sho-Pei; 2. CNAC luggage label (Pan Am Historical Foundation, Don Thomas Collection); Chinese 19th Route Army in defensive position in the Battle of Shanghai (1932) WWII database, (Wikimedia).

Clockwise from top, 1. Film frame of CNAC William Langhorne Bond with Peng Sho-Pei; 2. CNAC luggage label (Pan Am Historical Foundation, Don Thomas Collection); Chinese 19th Route Army in defensive position in the Battle of Shanghai (1932) WWII database, (Wikimedia).

Clockwise from top, 1. Film frame of CNAC William Langhorne Bond with Peng Sho-Pei; 2. CNAC luggage label (Pan Am Historical Foundation, Don Thomas Collection); Chinese 19th Route Army in defensive position in the Battle of Shanghai (1932) WWII database, (Wikimedia).

Clockwise from top, 1. Film frame of CNAC William Langhorne Bond with Peng Sho-Pei; 2. CNAC luggage label (Pan Am Historical Foundation, Don Thomas Collection); Chinese 19th Route Army in defensive position in the Battle of Shanghai (1932) WWII database, (Wikimedia).

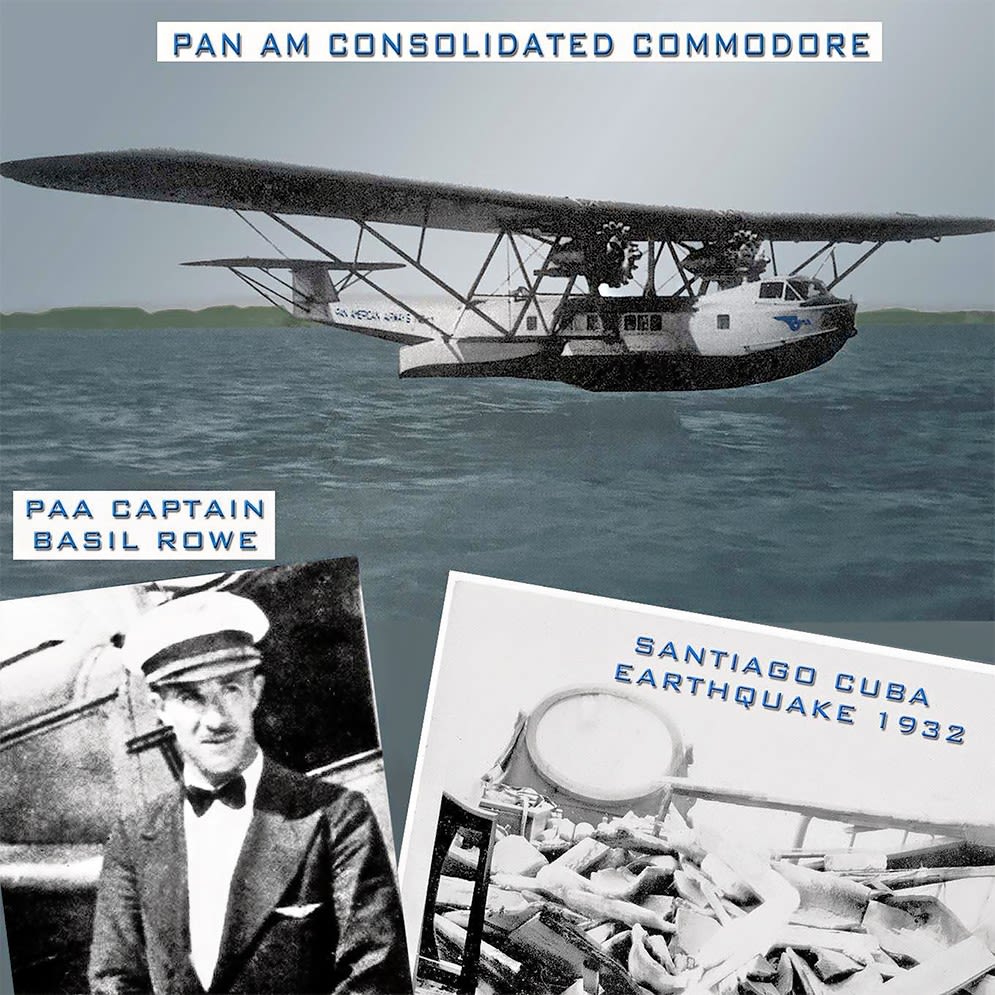

“Basil Brings Aid”

February 10, 1932

MIAMI — Wednesday, February 10, 1932. PAA Senior Pilot Basil Rowe’s 36th birthday barely registered because he was exhausted. For the past week he had flown emergency aid to Santiago de Cuba, on Cuba’s eastern end. On Wednesday, Feb. 3, the Caribbean tectonic plate wakened from a long slumber, triggering a 6.7 magnitude earthquake just south of the city. Santiago was rubble; inhabitants, including Pan American Airways’ personnel, were without a functioning hospital, firefighting/ambulance equipment, or food stores.

PAA’s Santiago de Cuba airfield and service facilities emerged unscathed because of recent upgrades, and all PAA employees soon reported to the airport. They were instructed to resume normal flight operations and to meet non-scheduled relief flights arriving as they could.

At 7:52 a.m. Basil Rowe lifted off Biscayne Bay in a spare Consolidated Commodore loaded with medical supplies and newspaper reporters. Pushing the aircraft to 100 mph and praying for a friendly tailwind to shorten the two-hour flight Rowe headed south. Meanwhile, PAA President, Juan Trippe, contacted the Cuban Government to announce these relief flights.

Two months later, “Pan American Air Ways,” published General Machado’s response so that PAA’s entire community was included:

‘In appreciation for this service, President Gerardo Machado of Cuba sent the following radio to Mr. J.T. Trippe, President of the Pan American Airways System:

Have just received your telegraphic message at a time when the Secretaries are holding a meeting. Members of the cabinet and I express to you in behalf of the Cuban Government and people our deepest appreciation of the generous action on the part of your company in sending its plane with assistance for Santiago de Cuba.

(Signed)

Gerardo Machado’

Source

Photo

“THE SENIORITY PUZZLE"

March 16, 1932

Pilot seniority lists are complex, particularly amidst rapid growth and personnel movement.

In its first fifteen months of existence, PAA hired four pilots: Edwin “Ed” Musick (June 1927), Hugh Wells (October 1927), Casper “Cap” Swinson (February 1928), Robert “Bob” Fatt (May 1928).

With the acquisition of West Indian Aerial Express on October 16, 1928, Basil Rowe & Donald Duke joined the roster. By the start of 1932 PAA employed forty pilots.

From the outset Ed Musick had served as Chief Pilot for all land plane pilots in the Caribbean Division; Basil Rowe had served as Chief Pilot for all sea plane pilots in the Caribbean Division. But with the 1932 equipment rationalization, and with the company’s continuing mergers and acquisitions, the seniority challenge intensified.

The answer arrived at was novel: Recognizing Basil Rowe’s years spent building and flying the pioneering commercial airline West Indian Air Express, he was named “Senior Pilot” (No. 1 on PAA’s pilot seniority list) and Ed Musick took the #2 slot, followed by Bob Fatt, “Cap” Swinson and Don Duke. Musick remained Chief Pilot for the Caribbean Division.

Informing its readers of this realignment, The Kingston, Jamaica "Daily Gleaner" (March 3, 1932, p. 20) told its readers:

“This is in no way a reflection on the record or the ability of Pilot Rowe, who it will be remembered, flew the American Clipper on her maiden flight from the plane yard to Miami, and acted as Co-pilot to Colonel Lindbergh when he flew the giant aircraft on the first flight to Cuba, Jamaica, Columbia and Panama.”

Basil Rowe sat atop PAA’s Pilot List for twenty-four years until his retirement in 1956!

Source

Photo

"NEW STATIONERY = MORE CUSTOMERS"

April 20, 1932

In the early 1930s, Pan Am was still largely dependent on US Post Office payments for international airmail contracts. Things had been improving financially, but income growth required more letter writers to accept airmail as a regular option. So in Spring 1932 PAA’s Mail Traffic Division launched a system-wide campaign to equate airmail with regular written correspondence. The hook: “Pan American Airways Bond,” special light weight writing paper and matching envelopes. As much as six sheets in a small envelope would weigh less than the one-half ounce limit provided for with an airmail stamp.

PAA’s Mail Traffic Division’s emotional pitch was straightforward:

“This service should give [airmail users] opportunity of writing lengthy letters without worrying about exceeding the weight limit.”

Order blanks for the new PAA watermarked stationery with matching envelopes bearing “Pan American Airways System” along with the winged-globe logo and distinctive blue and red stripes were sent out with samples. Soon the orders came flooding back. Before long Pan Am’s airmail stationery became the new standard for international airmail correspondence, which in turn boosted PAA’s foreign airmail carriage and payments from the US Post Office. In the process, PAA made money too.

Source:

Photo

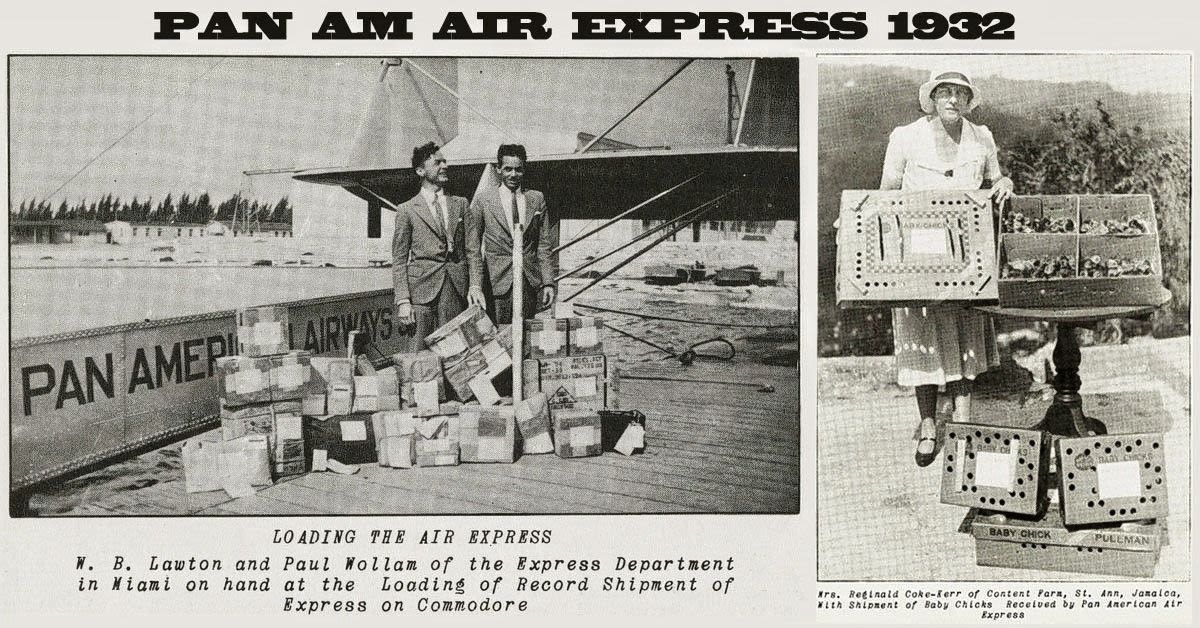

"FASHION, FEATHERS, AND FILM: AIR EXPRESS TAKES OFF"

May 25, 1932

Although neighborhood delivery vans carry larger loads today, international air freight was novel in 1932 … so much so that “Pan American Air Ways,” led its July 15th issue (Vol. 3, No. 3) with a piece dangling before its readers, “a gold medal which took the air to Bogota, and a chiffon dress rushed to a waiting maiden in Barranquilla,” to tantalize them with what was “beneath the string and wrapping paper” of southbound shipments.

In May 1932 Pan American Airways System’s New York office generated

• 509 pounds of Air Express shipments (a 64 lb. & 8 customer increase from April), a record that was cheered across the company.

• Miami’s May 22 Air Express alone, carried 13 units, valued at $5500 ($115,421 in 2020USD), weighing 257 lbs.

A description of Pan Am's cargo at that time:

“There in the corner in an apartment house of their own, a family of baby chicks on the way across the sky to Jamaica. That burlap covered package contains strawberry plants, carefully sodded, on their way to far-off Santos. Boxes filled with dresses being rushed by a smart Fifth Avenue shop to fair señoritas on the southern continent who want their fashions as new as they are in New York. Right alongside may be gear wheel replacements, serum upon whose speedy, safe delivery lives depend, samples of cosmetics from a New Jersey manufacturer, hatching eggs from a famous Mexican poultry farm, newsreels showing the latest pictures of the political convention in Chicago.”

The piece closed with a declaration that has not changed for over 90 years: “Business, these days, demands speed.” The air freight market grew, and within the year, Pan Am aircraft began flying freight-only charters for deep-pocketed companies and individuals.

Source and Photo

"The Curious Flock to Dinner Key"

June 30, 1932

Alongside baggage handlers, ticket agents, Customs officials, airmail processors, maintenance and flight personnel, Pan American Airways’ Dinner Key base employed an Official Guide to turn what “Pan American Air Ways,” (Vol. 3, No. 4.) described as “the constantly increasing army of visitors” from a nuisance into a marketing windfall.

The United States was a nation struck by aviation fever and, wanting to witness commercial aviation, people headed to Dinner Key in droves, even if they would never fly. So many tourists came that an enterprising Miami tour bus company ran a daily excursion to the facility.

Don Singer, Pan Am’s first Dinner Key guide reported that non-passenger foot traffic in June 1932 averaged 150 visitors a day and included “passengers from steamships stopping at Miami, convention and other groups, as well as local people and transient visitors. One of the larger groups was 280 delegates en route to a convention at Hollywood, Florida.”

Singer, and his assistants, guided the curious around the base describing Pan Am operations, extolling air travel’s virtues, and providing color commentary as aircraft landed and took off. Several times a year, Singer’s team enticed more-daring guests to buy a $3 30-minute Sunday afternoon sightseeing flight over Miami.

Source

Photo

"ANOTHER FIRST: STOWAWAY"

August 3, 1932

Robert Oliver Daniel “R.O.D./Rod” Sullivan flew Consolidated Commodore NC659M from Cristobal, Panama, Monday, June 27, 1932, four-hours east to Barranquilla, Columbia and five open-water-hours to Kingston, Jamaica, the overnight stop on Pan Am’s Panama - Miami route. Arriving Miami, Tuesday, an agricultural inspector discovered Mr. Paul Kaiser, a 177 pound Czechoslovakian, in the Commodore’s tail compartment.

Kaiser, Pan American Airway’s first stowaway, snuck aboard in Panama. “Pan American Air Ways” (Vol. 3 No. 3, July 15, 1932, p. 3.) reports, “after his arrival from Germany, [in Panama, and] unable to find work, [Kaiser] ran across a note in a local newspaper stating that auto manufacturing business was booming in Detroit. The obvious way to get to Detroit was "via Pan American." Jamaica’s “Daily Gleaner” claimed Kaiser “passed this port as an in-transit passenger on [a] Commodore a few weeks ago from Miami to Cristobal. It would appear Kaiser became stranded in the South American port, and was unable to pay his passage back to the United States.” Both source agree that Kaiser “was determined to get to Uncle Sam’s land.”

Deported to Panama aboard Commodore NC659M under Pan Am Captain Charles Lorber’s command, Paul Kaiser landed in Kingston, Sunday July 3, sitting in a passenger seat. While the crew spent the night at the posh Myrtle Hotel, Kaiser slept in Kingston’s jail … a step up from the Commodore’s tail. Arriving Panama, Monday afternoon, July 4, “local police … marched [Kaiser] up to jail for thirty days. ‘Loitering’ the judge called it.”

Sources

Photo

"Precious Cargo"

October 5, 1932

Labeled “express freight,” two bars of Sapolio soap left Buenos Aires, Argentina, in mid-1932 destined for 440 West Street, New York City, where Enoch Morgan’s Sons Co. executives waited to inspect its Argentine Sapolio factory’s first two bars.

In addition to heralding Buenos Aires’ outbound traffic, “Pan American Air Ways,” reported on arriving freight, telling readers that “each Pan American Grace plane” from Santiago, Chile, carried “a legally maximum load of ... splendid and succulent lobsters.” Nestled in a Panagra Ford Trimotor, the Pacific crustaceans crossed the Andes to an eager reception: “Each night after a plane arrives there is much boiling of pots and sizzling of grills in the swanky restaurants of Buenos Aires.”

Pan Am carried cargo even more-precious than soap or lobsters in 1932, however.

Lilian Aurora Blotner, (born April 10, 1932) reached Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Monday, June 20, aboard a Consolidated Commodore where she met her father, Felix M. Blotner, Pan Am’s Brazilian Division Operations Manager. Lillian left Camaguey, Cuba, her birthplace, on Tuesday, June 14 in Josefa Aurora Santalla Blotner’s lap, and “reached Rio on the seventy-second day of her life after a flight of 5,600 miles ... and arrived contented and cooing, apparently well satisfied with the efficiency and regularity of Pan American service.”

A few months later, Pilot Bert Sours scanned Rio’s sky for the Consolidated Commodore carrying his wife, Fernande, six-year-old daughter Denise, and five-year-old son Jackie (photo, right). This 7,000-mile Miami-to-Rio trip pushed the Sours kids’ miles-flown to over 11,000 miles in two years, a total matched by few humans in late-1932.

Lillian, Denise, and Jackie racked up tens of thousands of air miles during the years their fathers were stationed in South America. Emulating Felix Blotner and Bert Sours, for the next 60 years Pan Am employees across the globe entrusted their families to colleagues’ care.

Source

Photo

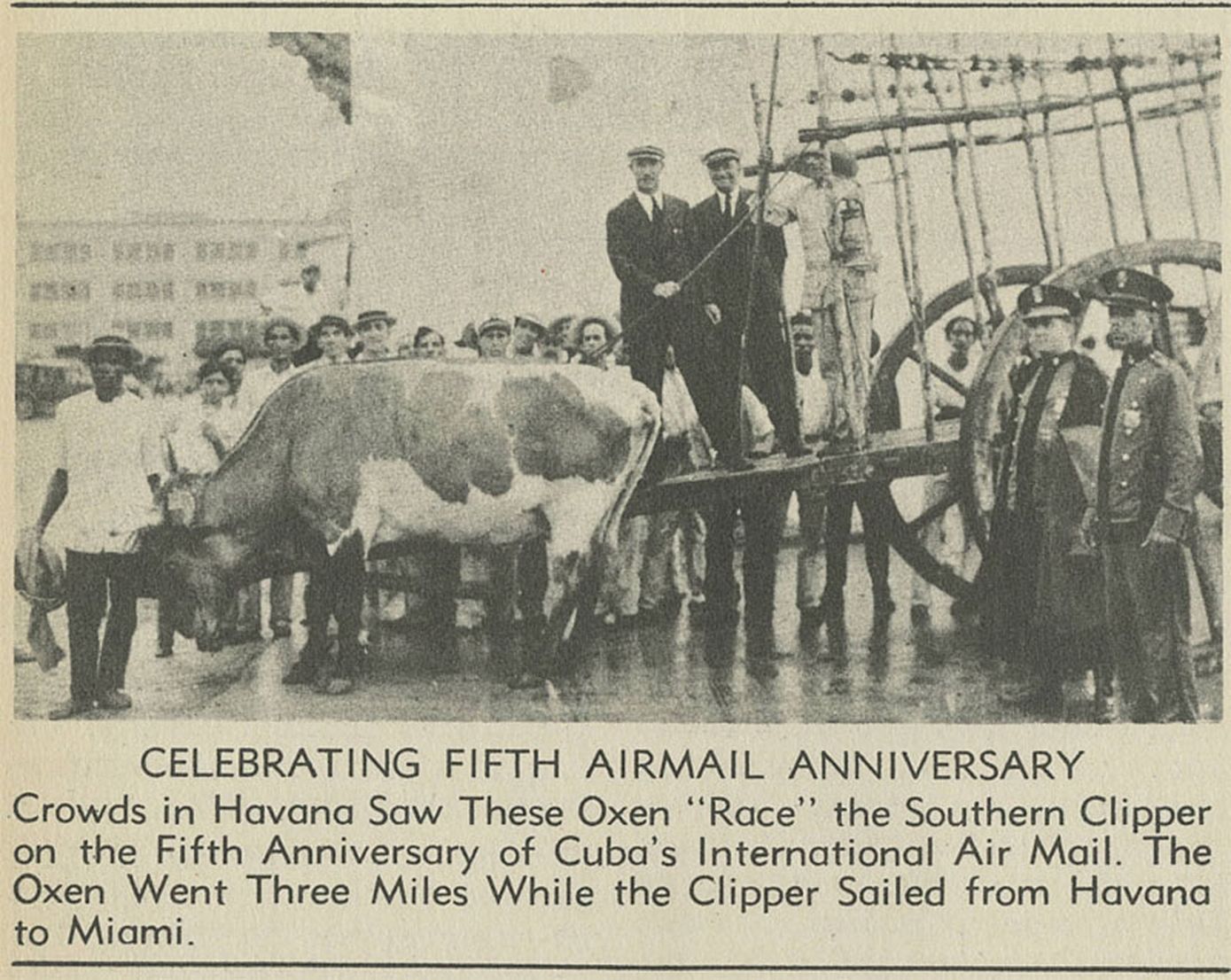

"Racing Cuban Bulls" On Pan Am's Fifth Airmail Anniversary

November 9, 1932

The Sikorsky S-40 “Southern Clipper” (NC752V) raced an oxcart to celebrate five years of Cuba-United States airmail service. Two bulls, following police and a marching band, pulled a wood-wheel cart three miles from Havana’s center along the waterfront to a point beyond the Paseo del Prado while the Sikorsky flew 227 miles to Miami. As he headed northeast, Pilot Basil Rowe looked down on Havana’s thronged Malecón certain of a win.

Twenty-four years later, Rowe admitted that the race was actually competitive “because of three factors… foremost was the method used by Cubans in handling oxen: goading them with a nail in the end of a pole. The second factor was a northeaster that I had to buck. The third was the Cuban… love of gambling.”

Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 "Southern Clipper" in flight.

Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 "Southern Clipper" in flight.

Headwinds held the S-40’s under its 115 miles-per-hour cruising speed while the oxen enjoyed a tailwind. “Everyone… betting against the Clipper… started to push the cart and pull the oxen until the poor beasts were doing about ten miles an hour and gaining on me.” As Rowe passed Key West, his radioman announced the cart had a mile and a half to go; Pan Am’s team was an hour-plus from Miami.” Unlike the ox, Basil had no one “sticking a nail into the tail of the Clipper.”

“Something had to be done,” stated Basil. “I couldn’t louse up the publicity. Besides, the Cubans had been two-timing me all the way,” so “I pulled the throttles closed and set … down on a smooth stretch of protected water in the lee of the Keys. I radioed ‘Just landed,’ planed along on the step for half a mile or so, then pulled up and continued the flight..."

“It was a dirty trick,” Basil admitted, “but so is sticking nails in oxen.”

Sources

Photo

“Christmas Crews Away from Home”

December 28, 1932

Pan American pilot, John H. “Gentleman Jack” Tilton, Jr. left 516 Hardee Rd., his Coconut Grove home before sunrise Saturday, December 24, 1932 for his two-mile commute to Pan Am’s Dinner Key seaplane base. Tilton’s wife, Gladys, and house staff, Elijah, Rosa Lee, and Matthew Lewis, would celebrate Christmas Day without him while he flew the Sikorsky S-40 Caribbean Clipper (NC81V) on the three-day Miami-Barranquilla-Miami route.

Jack and his crew were not Pan Am’s only employees working Christmas morning, 1932. Dinner Key was fully staffed: colleague R.O.D. Sullivan was commanding the Southern Clipper (S-40, NC752V) on the day’s Miami-Havana-Miami run. Havana was a more popular destination than Tilton’s stops -- Cienfuegos, Cuba, Kingston, Jamaica or Barranquilla, Columbia -- and Sullivan’s flight carried twenty-one passengers while Tilton headed south with five passengers, freight and mail.

The Caribbean Clipper landed in Kingston Sunday afternoon and tied up to the Pan Am barge at Bournmouth Bath alongside Sikorsky S-38B (NC9137). Elmer Rodenbaugh and his mechanic/radio operator joined Tilton’s crew for Christmas dinner at Kingston’s grand Myrtle Bank Hotel and turned in early as both crews faced early wake-up calls Monday morning.

Boxing Day, Monday, December 26, saw Rodenbaugh piloting the S-38B to San Juan, Puerto Rico and Tilton taking the Caribbean Clipper with one passenger to Barranquilla and returning with two. Back at the Grand Myrtle that night, Tilton joined pilot Gustave “Slim” Eckstrom -- in from San Juan in Sikorsky S-38B (NC9151) -- for dinner and a discussion of Tuesday’s weather forecast: by Tuesday night, Slim would sit for another hotel dinner in Port au Prince, Haiti, while Jack would join Gladys at home in Coconut Grove.

Source

Photo

STAY TUNED FOR MORE

"90 Years Ago"

Posts on Pan Am's early years of operations