OCEAN

CHALLENGE

ACROSS

THE ATLANTIC

1912-1919

FLYING BOATS

KEY PLAYERS

In April, 1913 The London Daily Mail newspaper offered a prize of £10,000 to anyone who could fly non-stop across the Atlantic — serious money, perhaps $1.8 million today.

John Cyril Porte, an experienced English aviator and aviation entrepreneur decided it was worth asking a rising star of US aviation — Glenn Curtiss, an "aero hydroplane" experimenter — if he would join in an effort to compete for the prize.

The partnership would result in something new: the flying boat. The basic design would shape the evolution of transoceanic aircraft for the next quarter of a century. An airplane that could cross an ocean, in the days before long, paved runways on land, needed a different surface from which to operate — the water.

To cross the Atlantic required major design improvements to early flying boats

The original form of the aircraft would evolve: Bi-planes would become monoplanes —engines would grow more powerful — cabins bigger, payloads and range greater. The carrying capacity would also expand with each new generation of flying boat, culminating in the design in 1938 of the magnificent Boeing B-314.

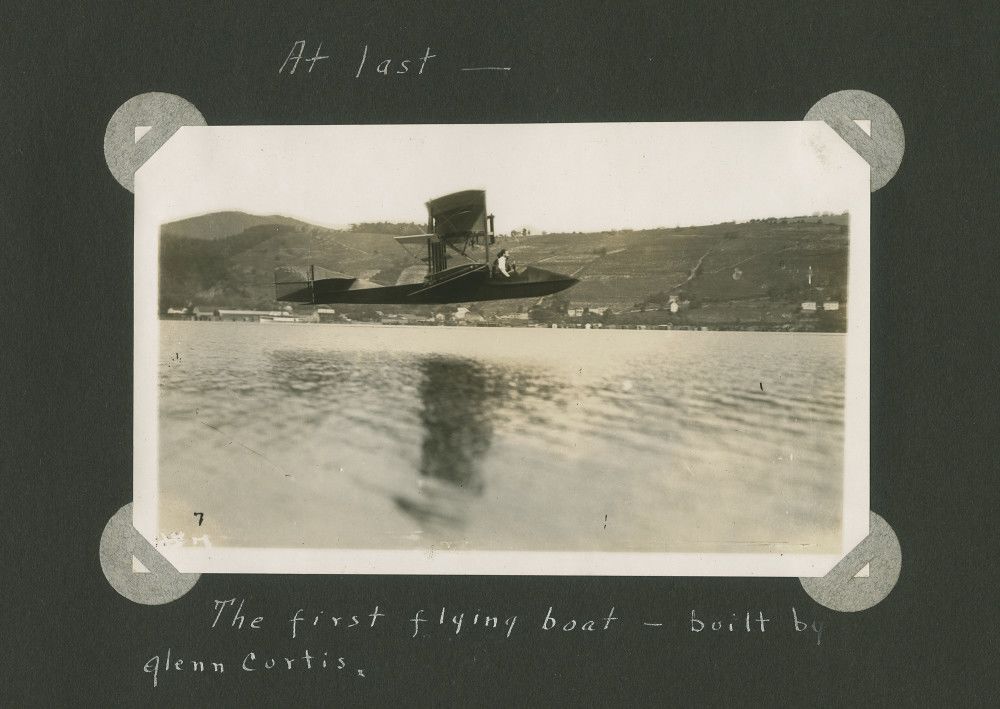

The innovative answer was the "step" a break in the otherwise smooth hull contour that made it possible for a flying boat to break free. The first design to benefit from this innovation was the "Flying Fish," that had been designed by Curtiss in 1912.

"At last — The first flying boat — built by Glenn Curtiss." Model E Flying Boat in Flight at Lake Keuka, Hammondsport, New York, c. 1912. Part of: George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection.

"At last — The first flying boat — built by Glenn Curtiss." Model E Flying Boat in Flight at Lake Keuka, Hammondsport, New York, c. 1912. Part of: George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection.

It was Porte who suggested a critical innovation to Curtiss as they collaborated on their new aircraft. Attaching wings to a boat, even with a streamlined hull, was not the whole answer. With all the power that could be coaxed out of the engines then available, Curtiss's early aircraft struggled to leave the water. An unseen force seemed to be keeping the would-be flying machine water-bound. The force was suction, developed as the speeding hull pushed water away from itself, resulting in a vacuum keeping the hull down, stuck to the water.

1914 "AMERICA"

Following the success of the "Flying Fish," Curtiss and Porte then turned their sights to creating an aircraft that could compete for the Daily Mail prize. Wealthy department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker of Philadelphia stepped in with an offer to support the venture. The first flight was to be an island-hopping affair, and would chart a course that would become familiar in the coming years —Newfoundland, then the Azores, then on to Europe to Plymouth, England.

Photo of "America" from the Library of Congress, shows aviators John Cyril Porte and George E.A. Hallett at a launch of the Curtiss Model H Flying Boat airplane "America" on June 22, 1914 in Hammondsport, New York. (Source: Library of Congress Flickr Commons project, 2011 and Glenn Curtis: Pioneer of Flight, Cecil R. Roseberry, 1991 ) Part of: George Grantham Bain Collection.

Photo of "America" from the Library of Congress, shows aviators John Cyril Porte and George E.A. Hallett at a launch of the Curtiss Model H Flying Boat airplane "America" on June 22, 1914 in Hammondsport, New York. (Source: Library of Congress Flickr Commons project, 2011 and Glenn Curtis: Pioneer of Flight, Cecil R. Roseberry, 1991 ) Part of: George Grantham Bain Collection.

The new craft was called "America." Work got underway in earnest in early 1914, at Hammondsport, New York, Glenn Curtiss's home base. The plane was larger than the "Flying Fish," with an enclosed cabin.

Initial tests showed the plane had a tendency to bury its nose in the water as speed increased. The fix was another innovation, one copied on many later flying boat designs: the "sponson." These "sea wings" provided hydrodynamic stability to keep the "America" on an even keel, as take-off neared.

Later, Sikorsky's flying boats, the Martin M-130s and Boeing B-314s of Pan Am would include sponsons.

Originals, restorations and replicas of many of Glenn Curtiss' flying boats (including "America') on display at The Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, NY.

Curtiss flying boat making 60 miles an hour, Bain News Service, publisher, glass negative. Photo probably shows the America, a "flying boat" produced by Glenn Curtiss, on the surface of Lake Keuka, New York State, July 12, 1914. (Source: Library of Congress Flickr Commons project, 2009).

Curtiss flying boat making 60 miles an hour, Bain News Service, publisher, glass negative. Photo probably shows the America, a "flying boat" produced by Glenn Curtiss, on the surface of Lake Keuka, New York State, July 12, 1914. (Source: Library of Congress Flickr Commons project, 2009).

The "America" Christening

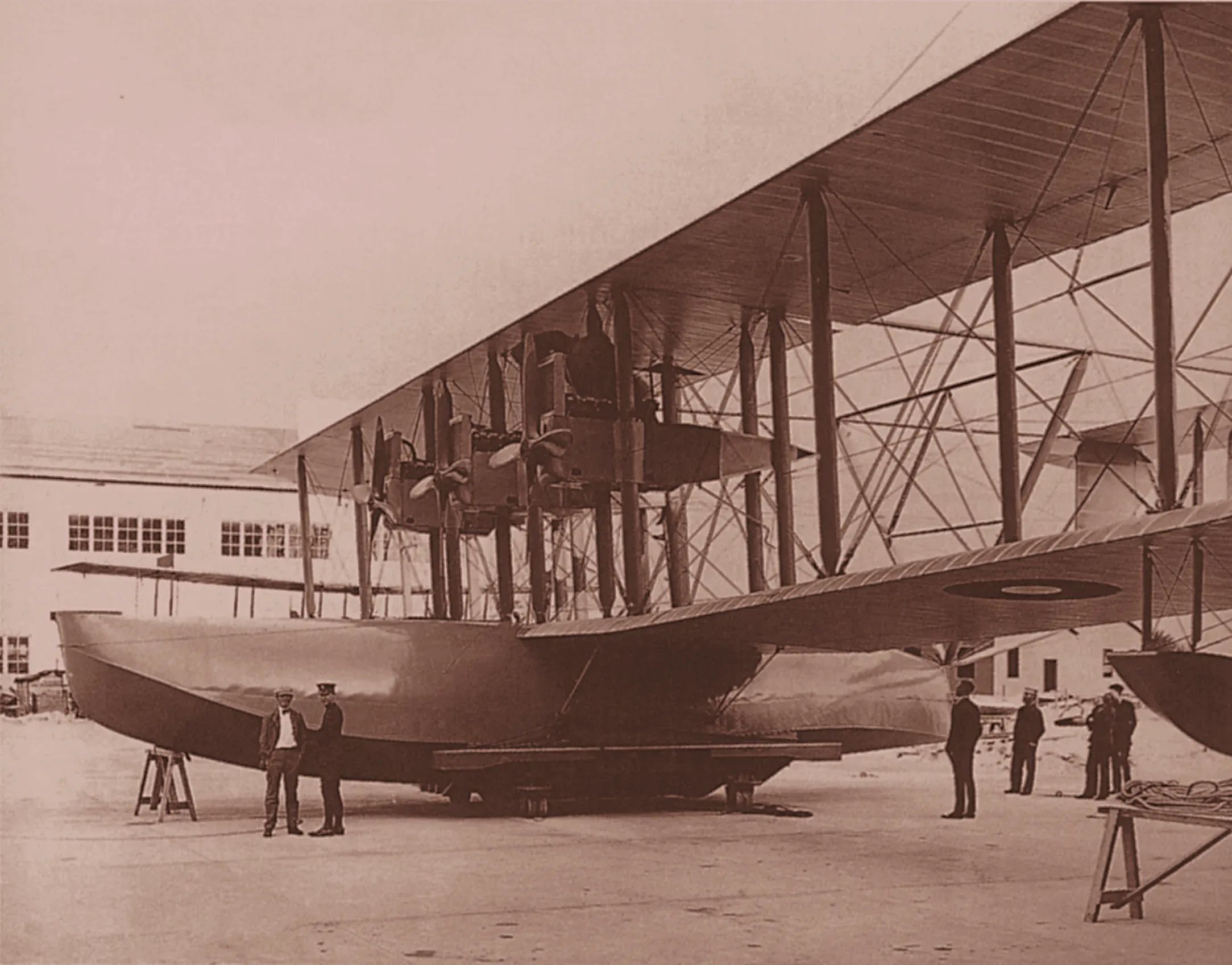

Assembling "America."Curtiss Model H Flying Boat airplane "America" June 1914, Hammondsport, NY. (Library of Congress, Flickr Commons 2011).

Assembling "America."Curtiss Model H Flying Boat airplane "America" June 1914, Hammondsport, NY. (Library of Congress, Flickr Commons 2011).

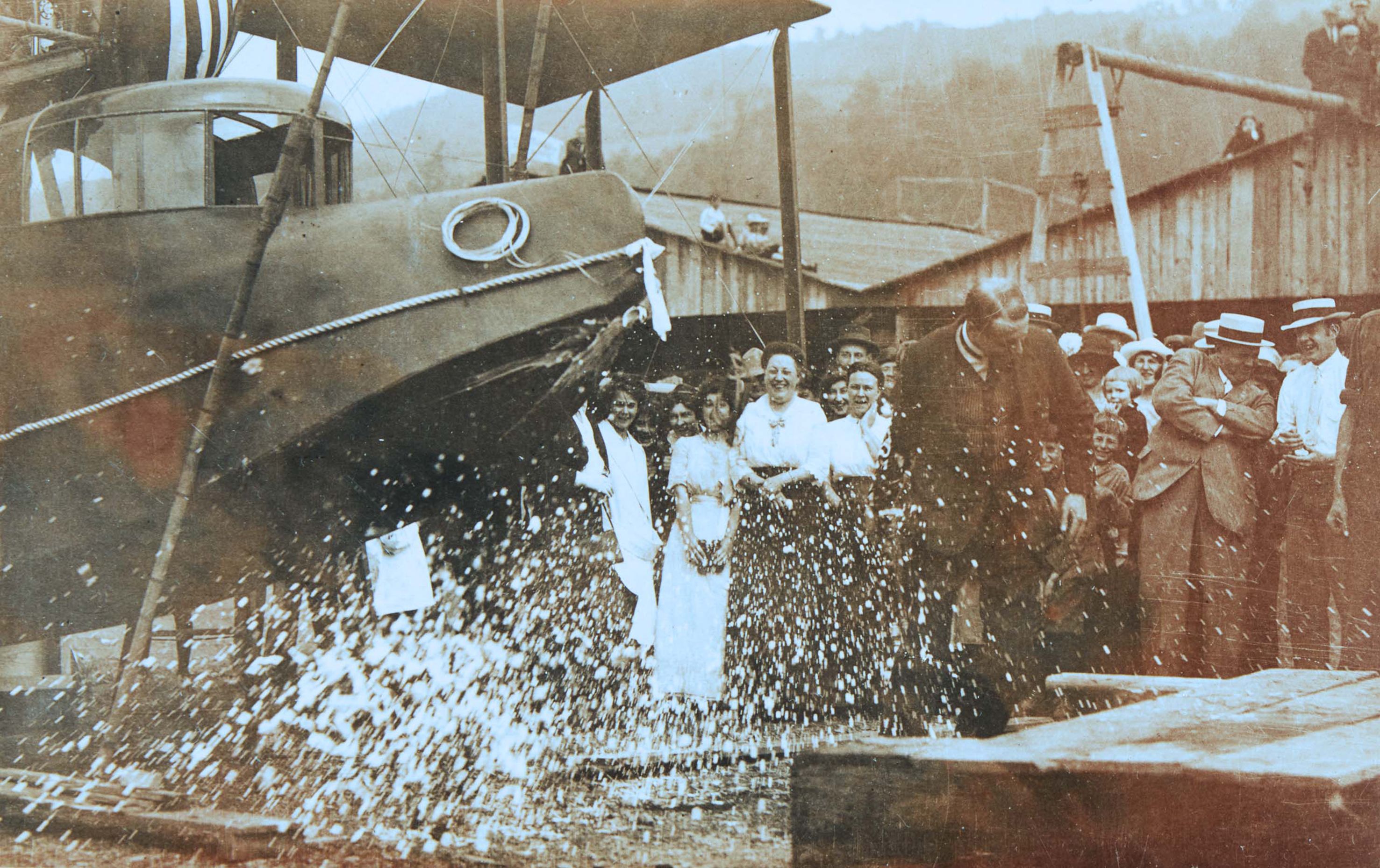

John Cyril Porte christens the "America" with a bottle of wine, June 23, 1914. (Courtesy Glenn H. Curtiss Museum).

John Cyril Porte christens the "America" with a bottle of wine, June 23, 1914. (Courtesy Glenn H. Curtiss Museum).

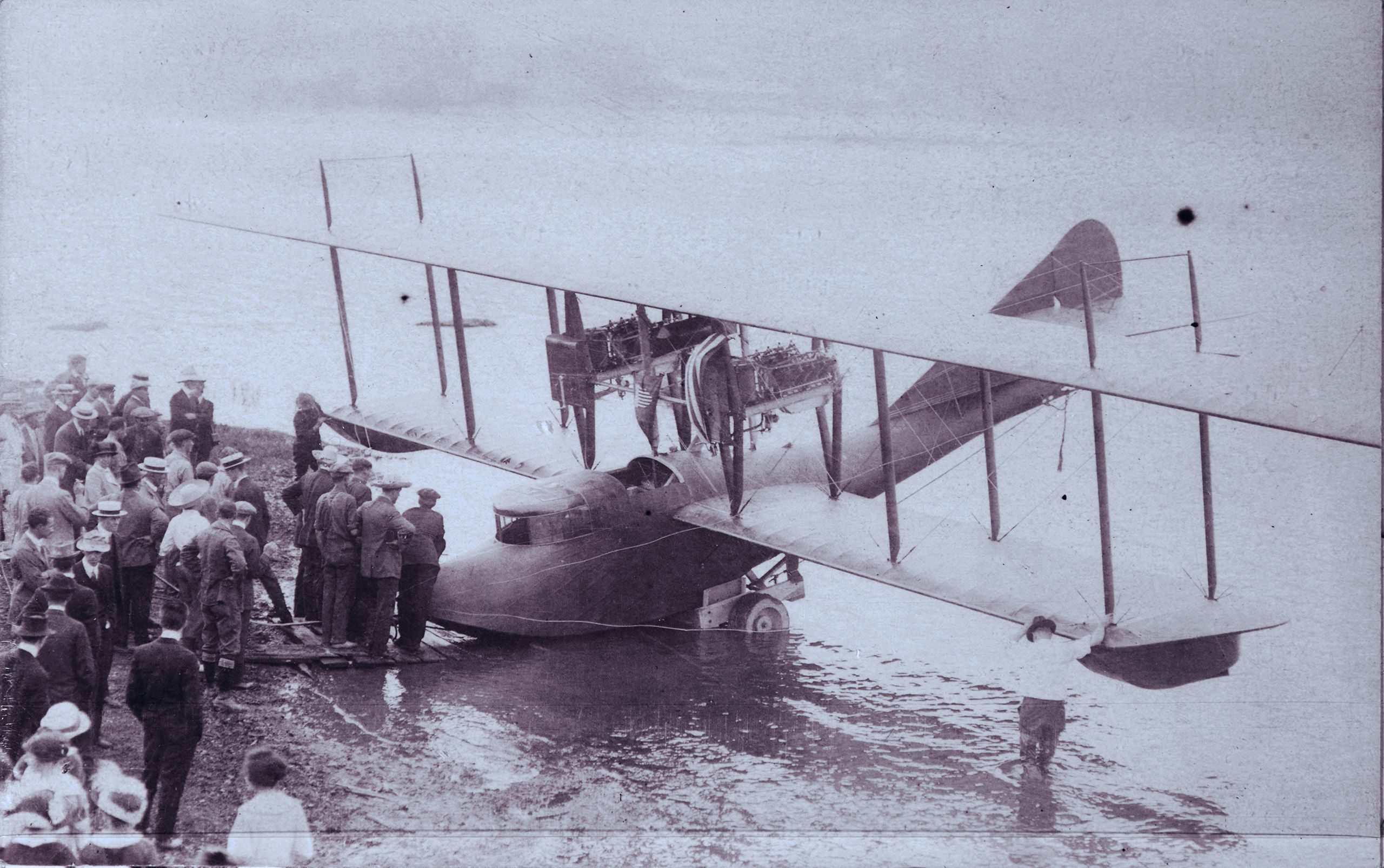

Crowd gathers to see the "America" flying boat c. 1914 (Courtesy of Glenn H. Curtiss Museum).

Crowd gathers to see the "America" flying boat c. 1914 (Courtesy of Glenn H. Curtiss Museum).

Curtiss Model H flying boat, "America" christening, June 23, 1914 (Courtesy of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum).

Curtiss Model H flying boat, "America" christening, June 23, 1914 (Courtesy of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum).

By July, 1914 planning was well underway for the flight, but the timing proved unfortunate. On August 4th, war was declared in Europe, and peacetime endeavors, such as first flight prize competitions, were put on the shelf for over four years. But the effort to create a transatlantic flying boat proved very timely.

Porte hastily booked passage to head back home to serve his country, and he came bearing a valuable military asset — the design for the "America." The flying boat was just what was needed to patrol the sea lanes around the British Isles, where German surface ships and submarines would be prowling, but also vulnerable to air attack.

Hundreds of "H" class flying boats and similar designs derived from the "America," were produced in Britain and the US for war service.

ENTER JUAN TRIPPE

Curtiss and Porte had more than proved their worth, and the potential for peacetime use was obvious, particularly to those with an eye on the future of aviation.

One of those was Juan Trippe, who had flown Curtiss-designed flying boats as a US Navy pilot. He was well aware of the ocean-spanning possibilities of flying boats when he returned to Yale after his military service.

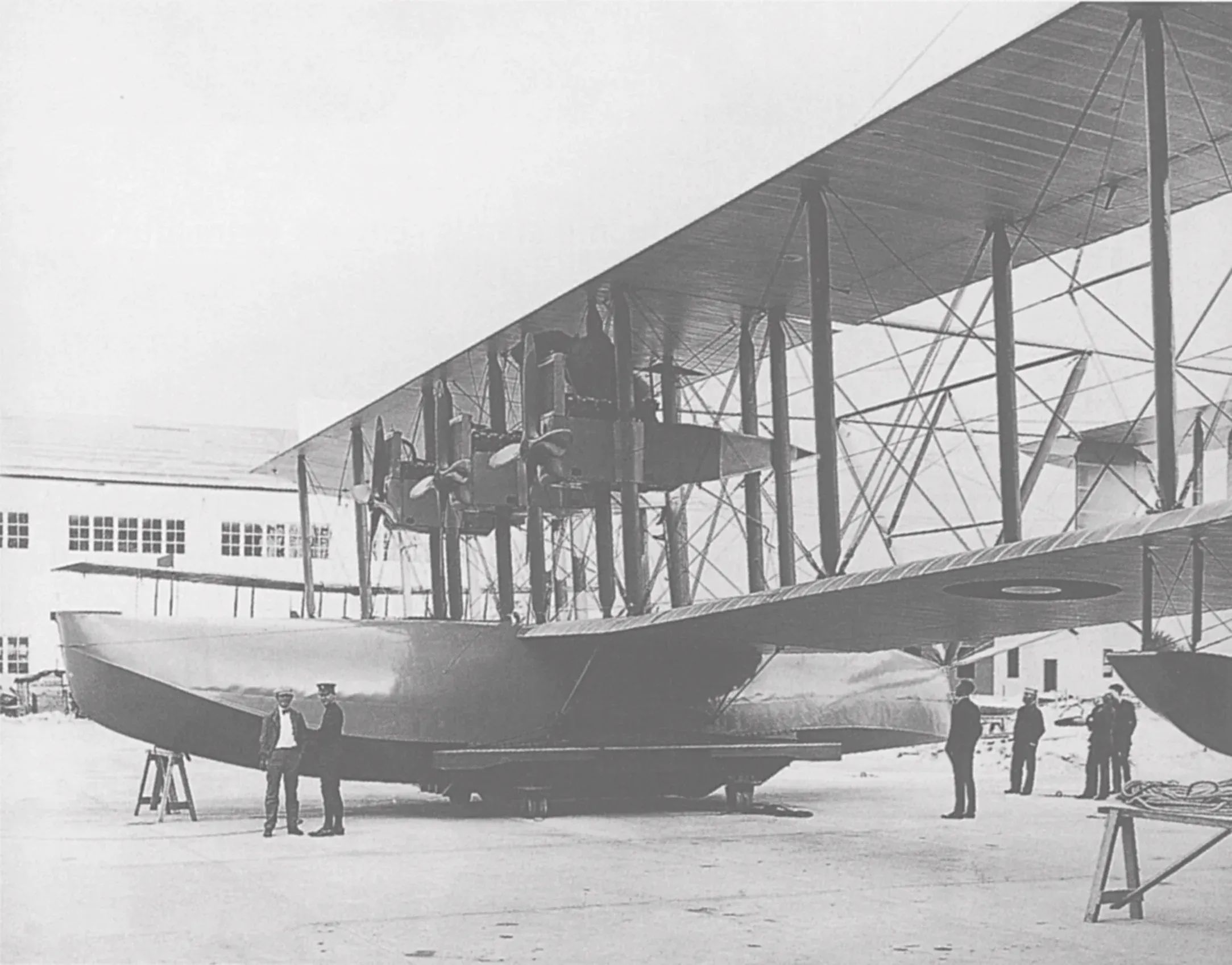

And with war's end, the US Navy found itself with a small fleet of advanced flying boats produced too late to be of service in the conflict. These "NC" (for Navy-Curtiss) seaplanes were big and long-ranged. The Navy wanted to display their capabilities in a demonstration flight along the route planned for their forebear the "America" by Curtiss and Porte.

The "NCs" would make their way to Newfoundland, thence to the Azores, and then on to Lisbon and afterwards, Plymouth, England.

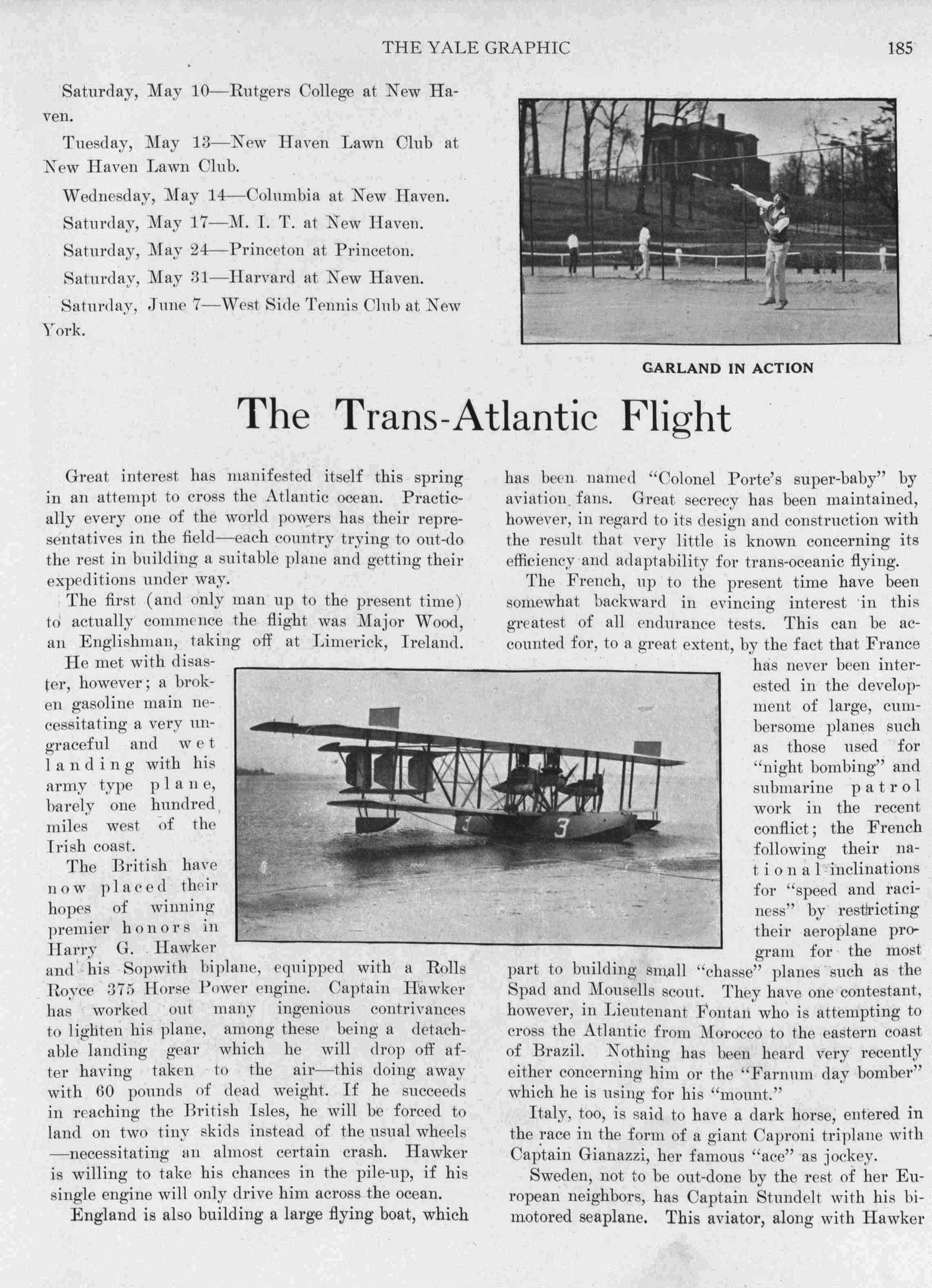

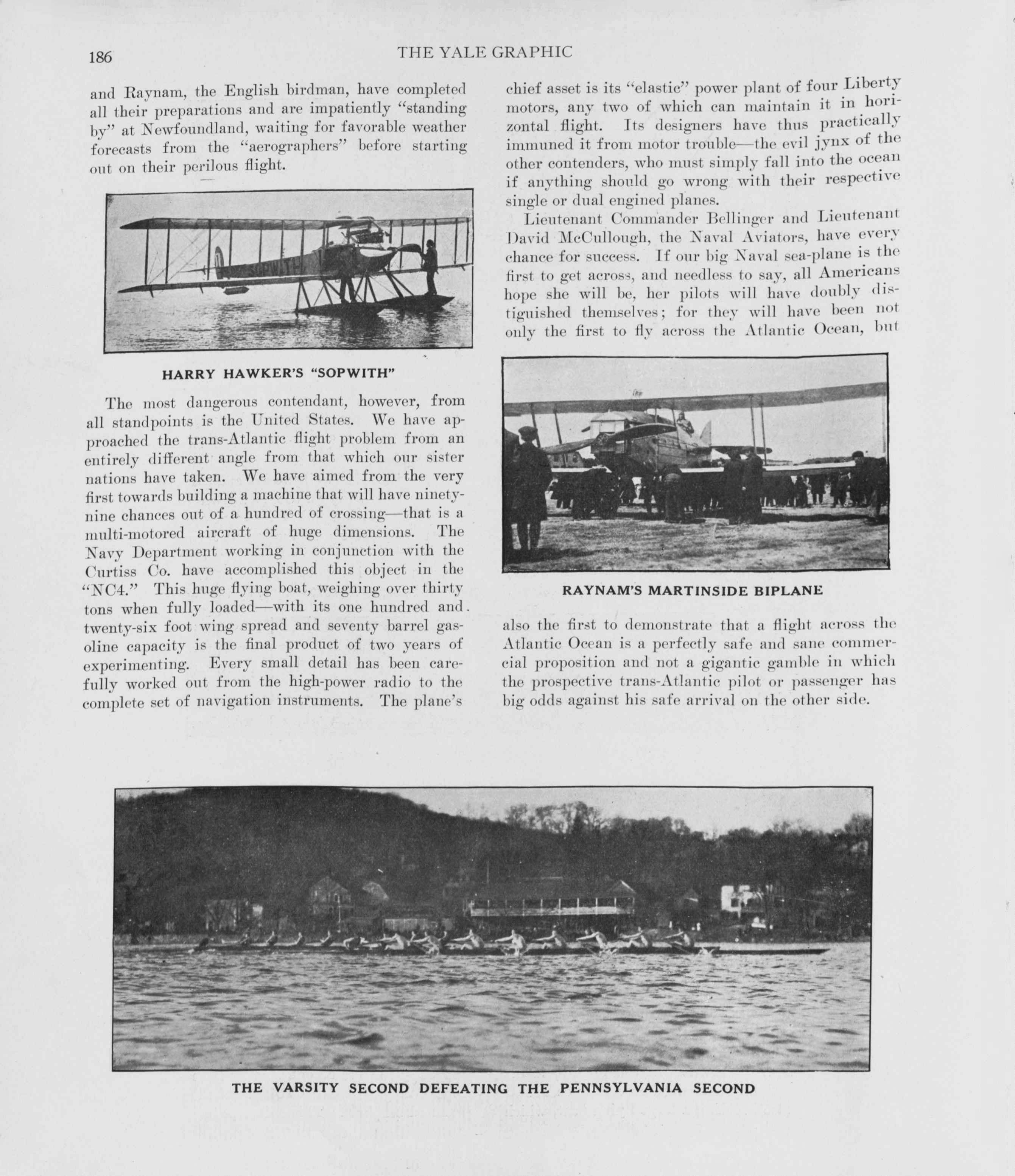

Just before the flight, planned for May 1919, an enthusiastic article discussing the possibility of transoceanic aviation appeared in the Yale Graphic Magazine. The article was unsigned, but we know now who wrote it: Juan Trippe.

The Yale Graphic, May 7, 1919, pp. 185-186. Courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The Yale Graphic, May 7, 1919, pp. 185-186. Courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

"If our big Naval sea-plane is the first to get across, and needless to say, all Americans hope she will be, her pilots will have doubly distinguished themselves; for they will have been not only the first to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, but also the first to demonstrate that a flight across the Atlantic Ocean is a perfectly safe and sane commercial proposition and not a gigantic gamble in which the prospective trans-Atlantic pilot or passenger has big odds against his safe arrival on the other side."

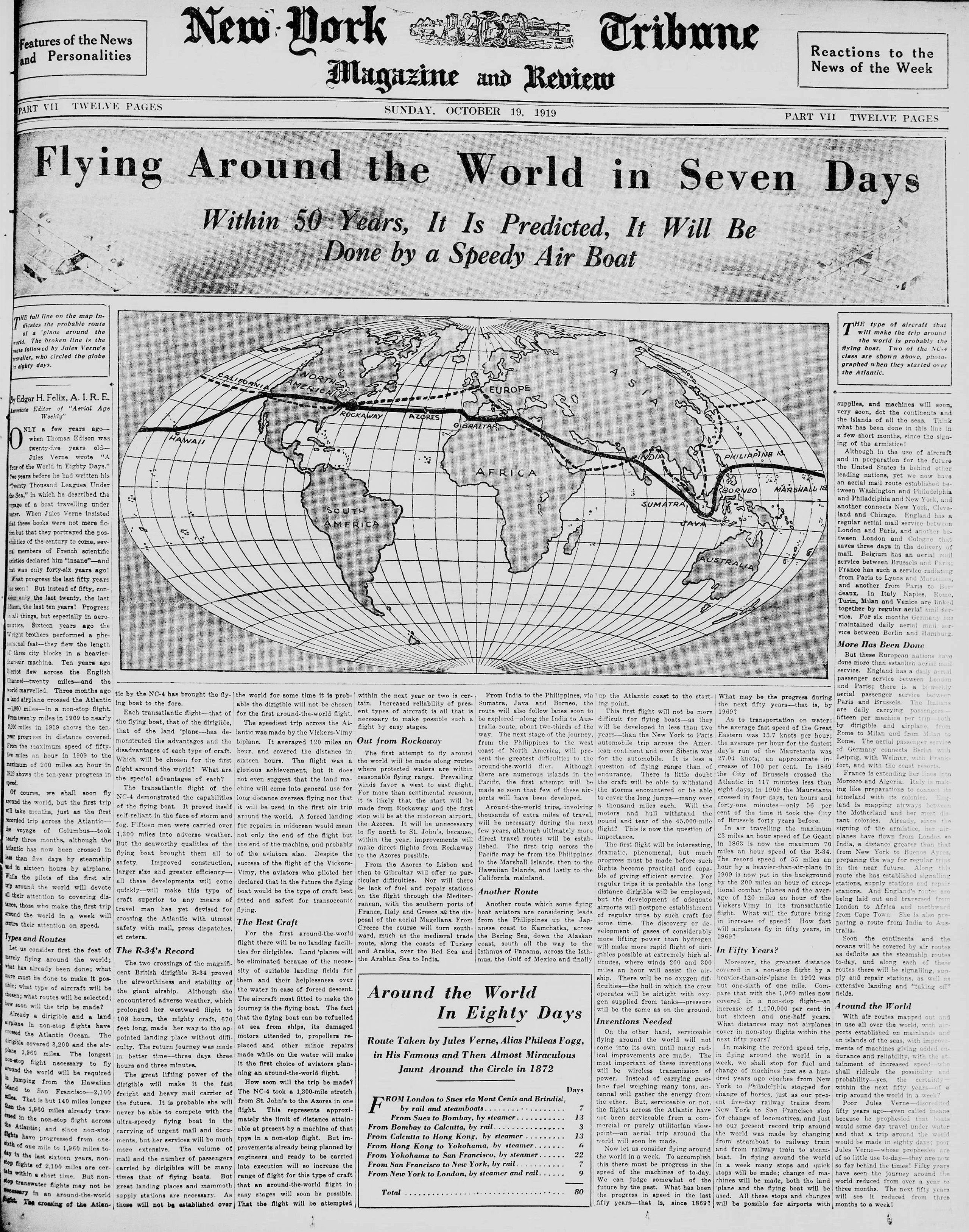

Just five months after Juan Trippe wrote his article in the Yale magazine, The New York Tribune published a front page feature predicting that in 50 years, flights would embark from Rockaway to the Azores, and fly around the globe in just seven days.

"The type of aircraft that will make the trip around the world is probably the flying boat." — New York Tribune, October 19, 1919.

New York Tribune, October 19, 1919 (Chronicling America, Library of Congress).

New York Tribune, October 19, 1919 (Chronicling America, Library of Congress).

1919 — THE STORY OF THE CURTISS-NAVY "NC's"

During the First World War, Glenn Curtiss collaborated with the Navy on the design of flying boats operated by British and Americans to patrol and protect coastal waters

VIDEO

Launching of Curtiss-designed flying boats for submarine-hunting patrols in the Great War required plenty of manpower, c. 1918 (National Archives, US Navy Department film).

Launching of Curtiss-designed flying boats for submarine-hunting patrols in the Great War required plenty of manpower, c. 1918 (National Archives, US Navy Department film).

Glenn Curtiss and his firm, Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company, continued collaborations with the Navy to improve flying boat designs for long-range flights on anti-submarine patrols.

FIRST TO FLY OVER THE VAST ATLANTIC: THE NC-4

Curtiss NC-1 in October 1918 with the initial three engine configuration (Library of Congress).

Curtiss NC-1 in October 1918 with the initial three engine configuration (Library of Congress).

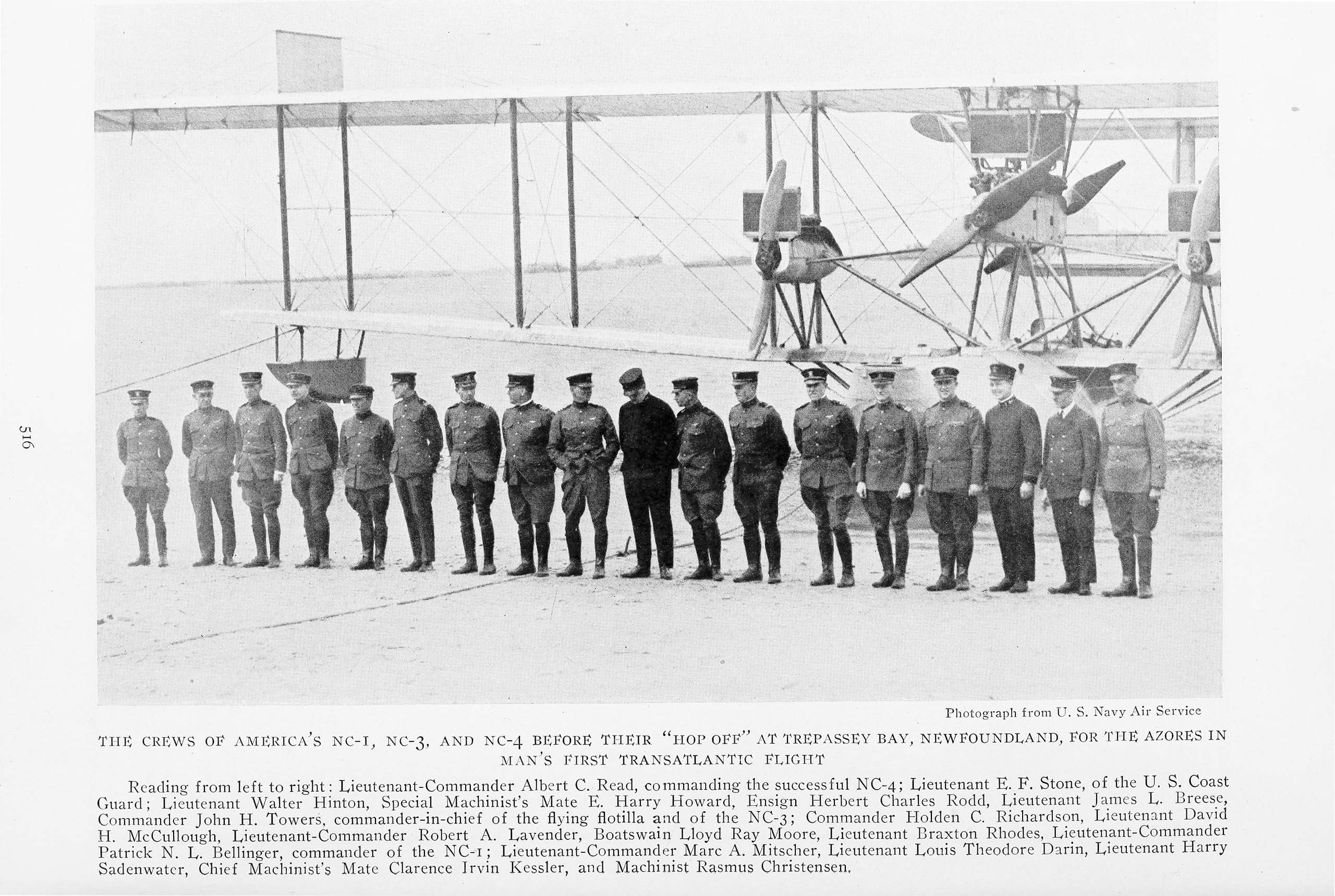

Crews of the three transatlantic NCs before taking off, National Geographic Magazine, 1919 (Biodiversity Heritage Library via Wikimedia) https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/44502

Crews of the three transatlantic NCs before taking off, National Geographic Magazine, 1919 (Biodiversity Heritage Library via Wikimedia) https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/44502

Even before their famous flight across the Atlantic, the original four Curtiss-Navy "NCs" were unfortunately reduced from four to three due to mechanical issues.

May 8, 1919, three NC's slated for the trip, each with six crew members, departed from Rockaway, New York. During their flight across the ocean, two of the flying boats were forced down at sea.

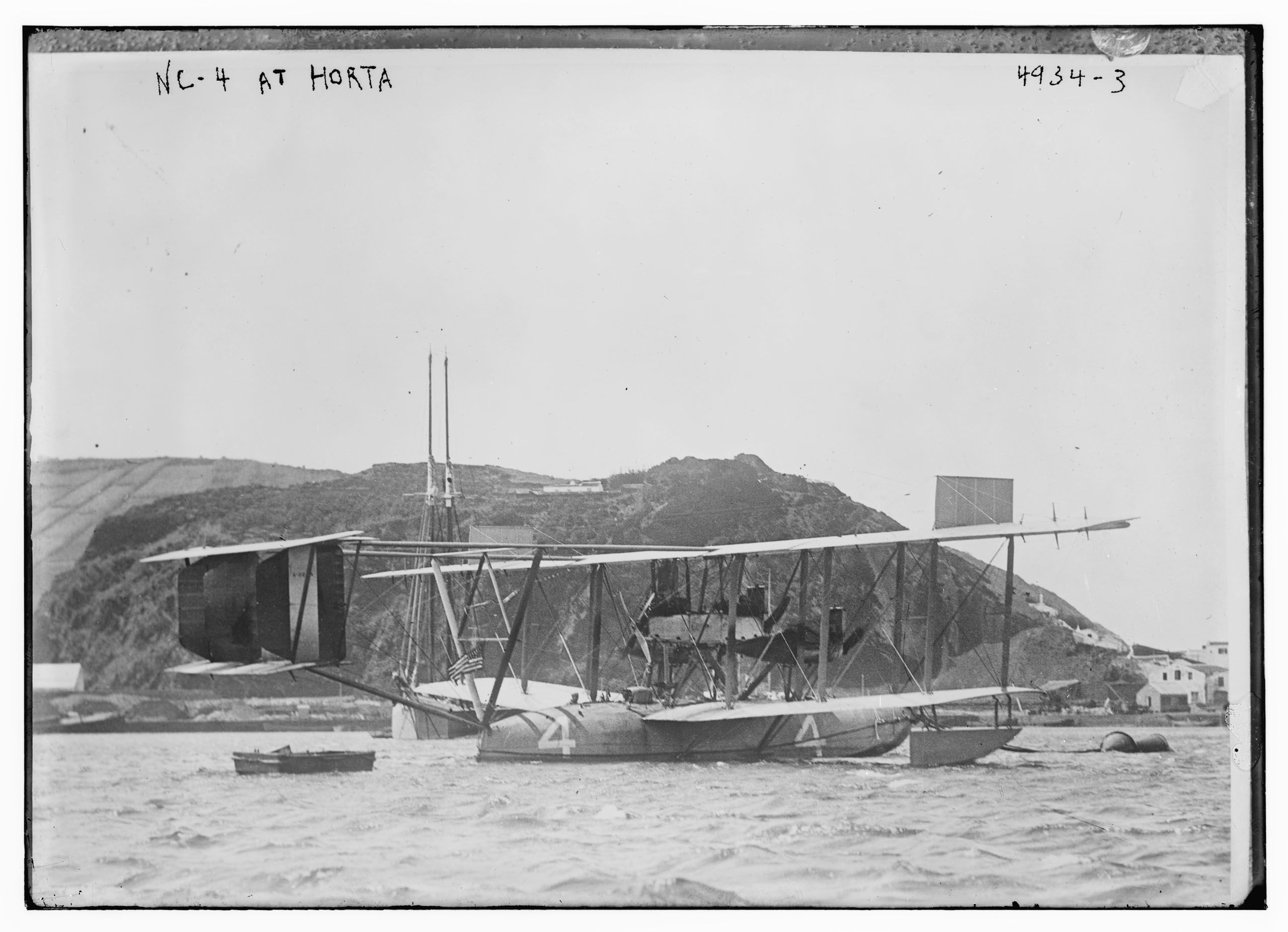

But good fortune smiled on the remaining plane, NC-4, and it flew the entire route to Plymouth, England, stopping at the Azores and Lisbon despite maintenance issues and weather-related setbacks .

Photo: Curtiss NC-4, having arrived at Horta, Azores on its transatlantic flight in May 1919 (Library of Congress).

Photo: Curtiss NC-4, having arrived at Horta, Azores on its transatlantic flight in May 1919 (Library of Congress).

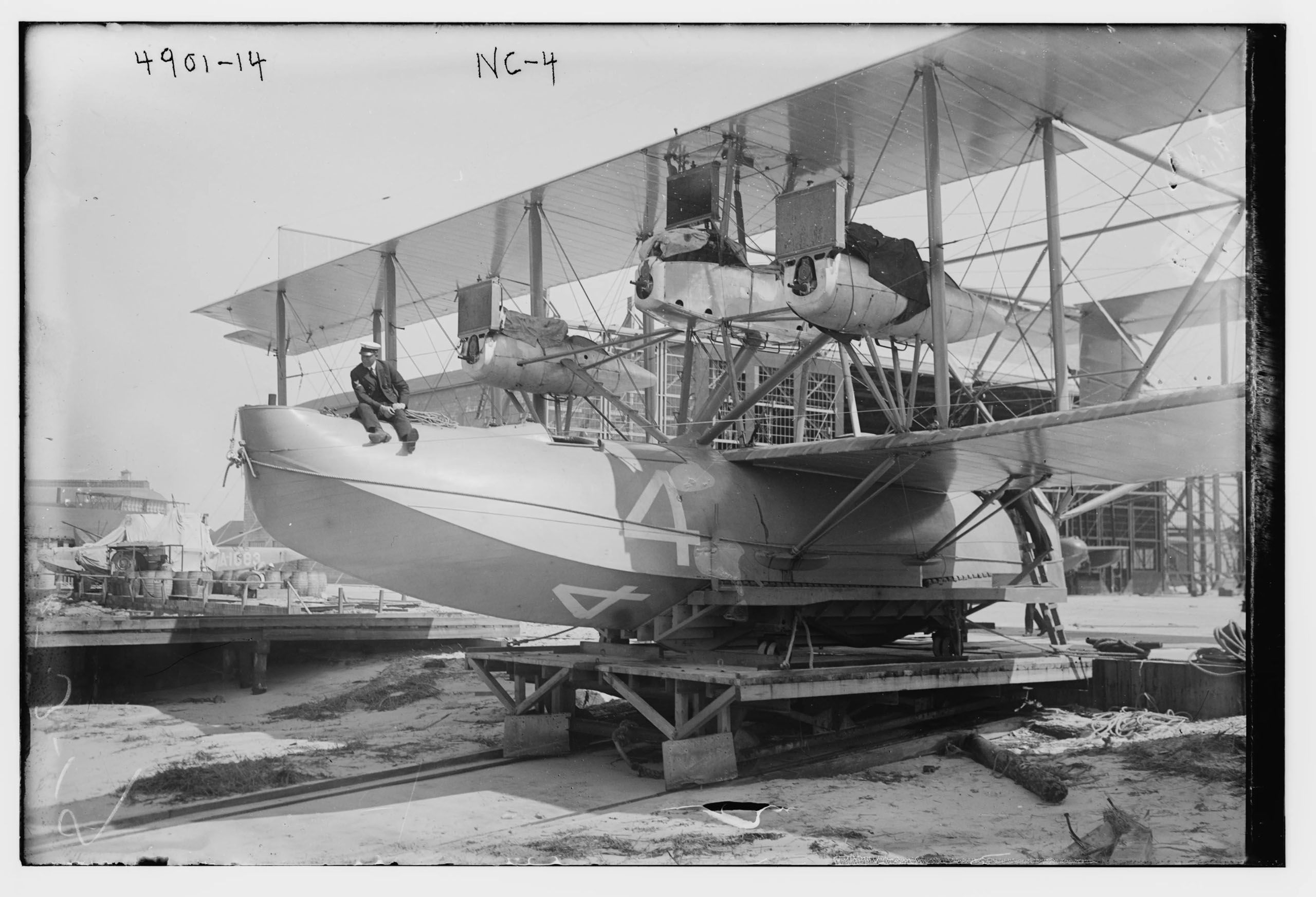

Photo: NC-4 prior to its transocean trip, at Rockaway Beach (Library of Congress).

Photo: NC-4 prior to its transocean trip, at Rockaway Beach (Library of Congress).

NC-4 JOURNEY

Tremendous acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic

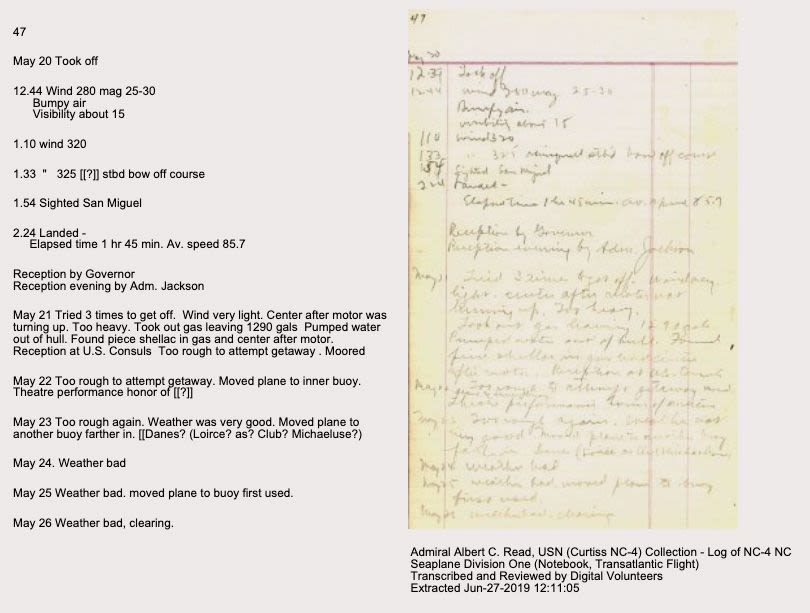

All three NC flying boats were compelled to deal with rough, stormy seas and wind. But the NC-4 flying boat stayed the course, with a top speed of only 85 mph, making it to its final destination under the command of Albert Read.

May 20, 1919 entry in the Log of NC-4 Seaplane, Albert C. Read, commander, indicated bad weather in the Azores. (Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archives).

May 20, 1919 entry in the Log of NC-4 Seaplane, Albert C. Read, commander, indicated bad weather in the Azores. (Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archives).

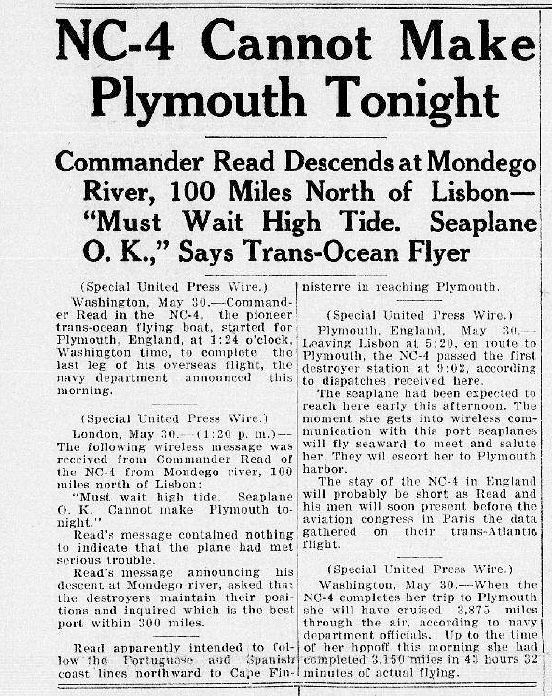

Friday, May 30, 1919, Butte Daily Bulletin: "Commander Read Descends at Mondego River, 100 Miles North of Lisbon -- 'Must Wait High Tide. Seaplane O.K.' Says Trans-Ocean Flyer" (Library of Congress, Chronicling America).

Friday, May 30, 1919, Butte Daily Bulletin: "Commander Read Descends at Mondego River, 100 Miles North of Lisbon -- 'Must Wait High Tide. Seaplane O.K.' Says Trans-Ocean Flyer" (Library of Congress, Chronicling America).

As the world eagerly awaited news, the NC-4 proceeded carefully. Commander Read and his crew would finally complete their mission after waiting several days in the Azores for safe flying conditions, and by keeping an eye on the tides in Lisbon.

They accomplished the final leg of their journey from Portugal, landing in Plymouth, England on the 31st of May, 1919 after a long, arduous trip.

NC-4 TODAY

"One hundred years from now museum sightseers will stand before the 'NC-4,' the first flying boat to cross the Atlantic."

As predicted, we can still see the actual NC-4 that flew the Atlantic in 1919, now displayed at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

Curtiss flying boat NC-4 on display at the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola Florida. Date: 28 December 2017, by Signalcharlie, Wikimedia Commons (CC)

TRANSATLANTIC PRIZES

1919 was a portentous year for transatlantic flight. While NC-4 was still in flight to Europe, a New York hotel owner, Raymond Orteig, promised a prize of $25,000 for the first flight from New York to Paris, although there no takers until Charles Lindbergh's flight in 1927.

BI-PLANE AVIATORS WIN THE DAILY MAIL PRIZE

The Daily Mail's £10,000 prize (offered in pre-war 1913) was still unclaimed

ALCOCK & BROWN

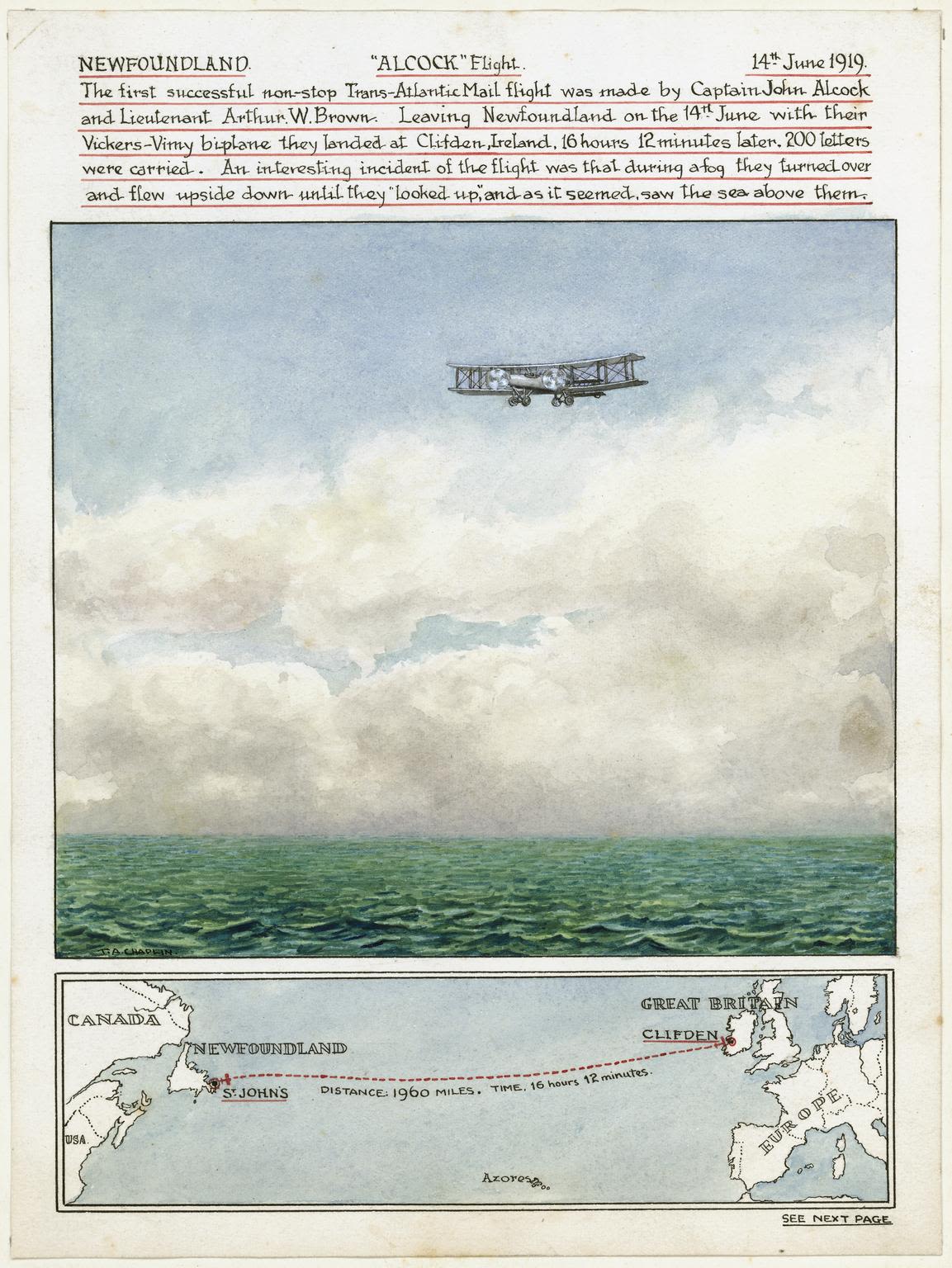

Less than two weeks after the NC-4 completed its flight, two fearless British flyers John Alcock and Arthur Brown finally claimed the Daily Mail prize. They were the first to fly non-stop from Newfoundland to Ireland in their small Vickers-Vimy biplane. Their adventures included upside down flying, and landing in a bog near Galway.

Manuscript water colour drawing with map and text celebrating the 'Alcock' flight on the 14th June 1919 Flight. (Science Museum Group, UK) https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/alcock-and-brown#the-brave-aviators&gid=1&pid=6

Manuscript water colour drawing with map and text celebrating the 'Alcock' flight on the 14th June 1919 Flight. (Science Museum Group, UK) https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/alcock-and-brown#the-brave-aviators&gid=1&pid=6

On Display, Alcott & Brown's Vickers-Vimy Biplane, 1919. (Courtesy of the Science Museum Group, Creative Commons License).

On Display, Alcott & Brown's Vickers-Vimy Biplane, 1919. (Courtesy of the Science Museum Group, Creative Commons License).

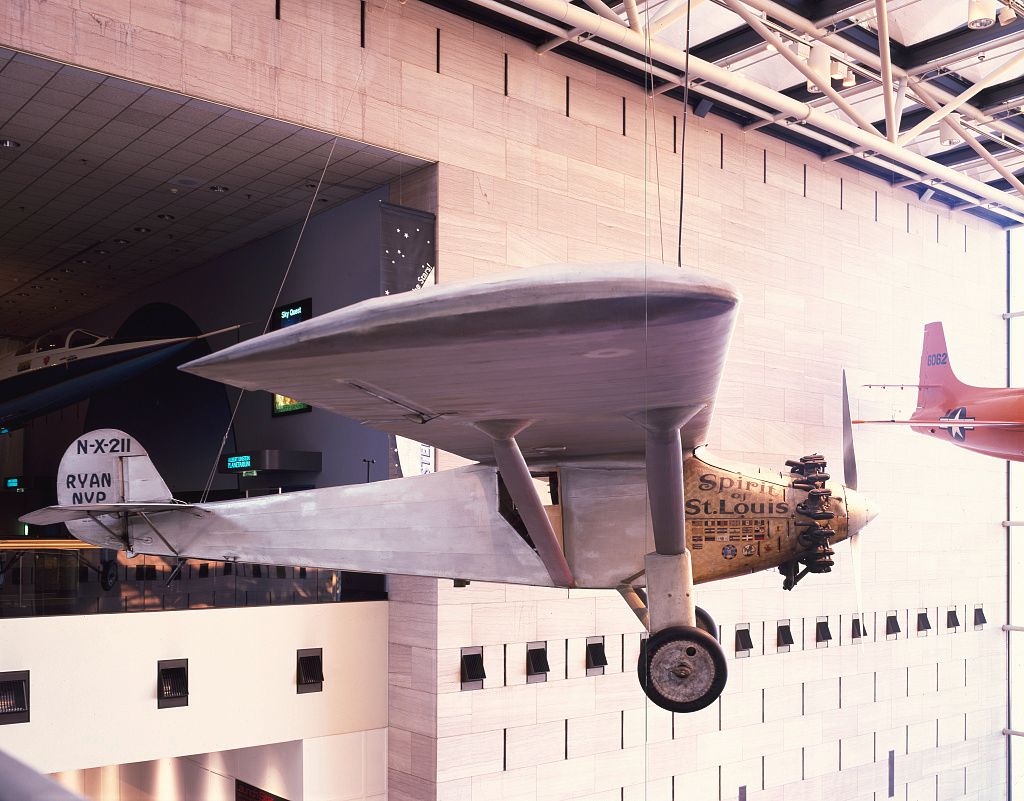

LINDBERGH WINS THE ORTEIG PRIZE

The transatlantic flights of 1919 were harbingers of events to come. But they would be some time in coming. It wasn't until Charles Lindbergh made his epochal flight from Long Island to Paris in May, 1927 in his custom-built monoplane, that Orteig's $25,000 prize was finally claimed.

Lindbergh's "Spirit of St. Louis" hanging at the Smithsonian Insitution's Air and Space Museum on the National Mall, Washington DC. (Library of Congress photo).

Lindbergh's "Spirit of St. Louis" hanging at the Smithsonian Insitution's Air and Space Museum on the National Mall, Washington DC. (Library of Congress photo).

IT WAS THEN THAT THE PACE OF TRANSATLANTIC AVIATION REALLY PICKED UP

News coverage of Charles Lindbergh's momentous flight from New York to Paris, 1927 (Fox News) from Archive.org

News coverage of Charles Lindbergh's momentous flight from New York to Paris, 1927 (Fox News) from Archive.org