WARTIME LEGACIES

The war was over, and it was a "job well done" for Pan Am. But there were a lot pieces to be picked up afterwards. The 1945 Annual Report published a roll of honor listing 192 employees who had given their lives during war. The flying boats that had served a vital need for almost twenty years had now flown off into the proverbial sunset.

"The war has been a bitter laboratory for air transport but a laboratory nonetheless. Wartime research, and inventions will be reflected not only in improved passenger transportation but also in faster air-mail schedules and in lower cost cargo transport" (Pan American Airways 1943 Annual Report, p. 25).

NEW AIRCRAFT - NEW TECHNOLOGIES - NEW COMPETITION

In January 1945, limited commercial service to Europe was re-established, and would soon be picking up

The outlook for revived Atlantic business was supported by the news that 22 new Constellations would be joining the fleet, along with 45 Douglas DC-4s.

Pan Am Lockheed Constellation (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

Pan Am Lockheed Constellation (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

1946: Four Pan American Airways Constellations lined up at LaGuardia Field, New York City, not far from the Marine Air Terminal (Walter Christensen collection).

1946: Four Pan American Airways Constellations lined up at LaGuardia Field, New York City, not far from the Marine Air Terminal (Walter Christensen collection).

VIDEO

On the first commercial flight after WW2 to Prague and Vienna, Juan Trippe arrives in Tulln Airport in 1946 aboard a Pan Am L-049 Constellation (US National Archives).

On the first commercial flight after WW2 to Prague and Vienna, Juan Trippe arrives in Tulln Airport in 1946 aboard a Pan Am L-049 Constellation (US National Archives).

Panagra Douglas DC-4 Cutaway (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

Panagra Douglas DC-4 Cutaway (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

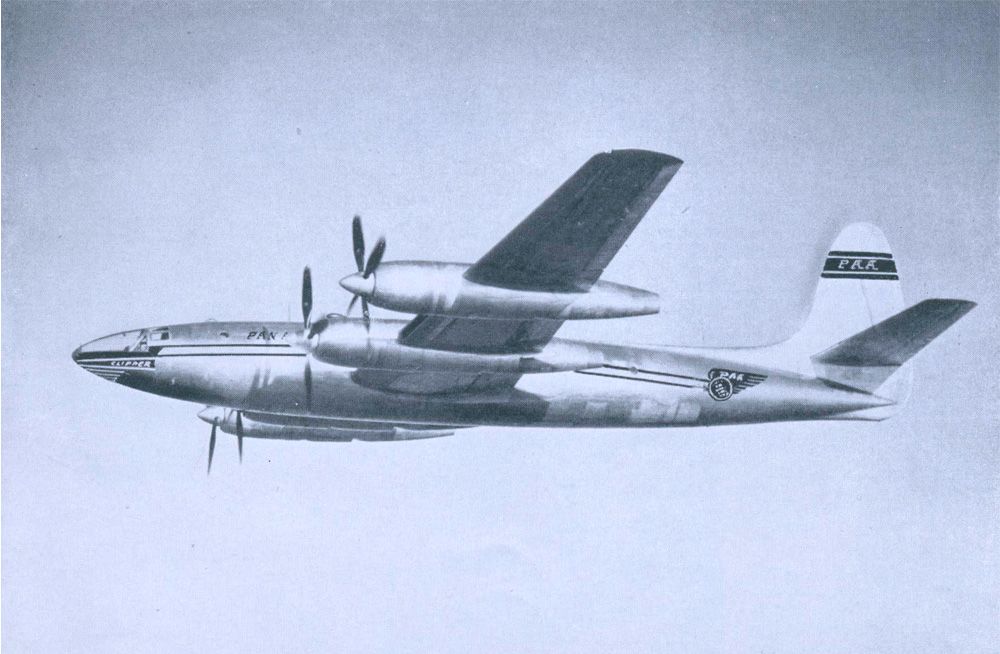

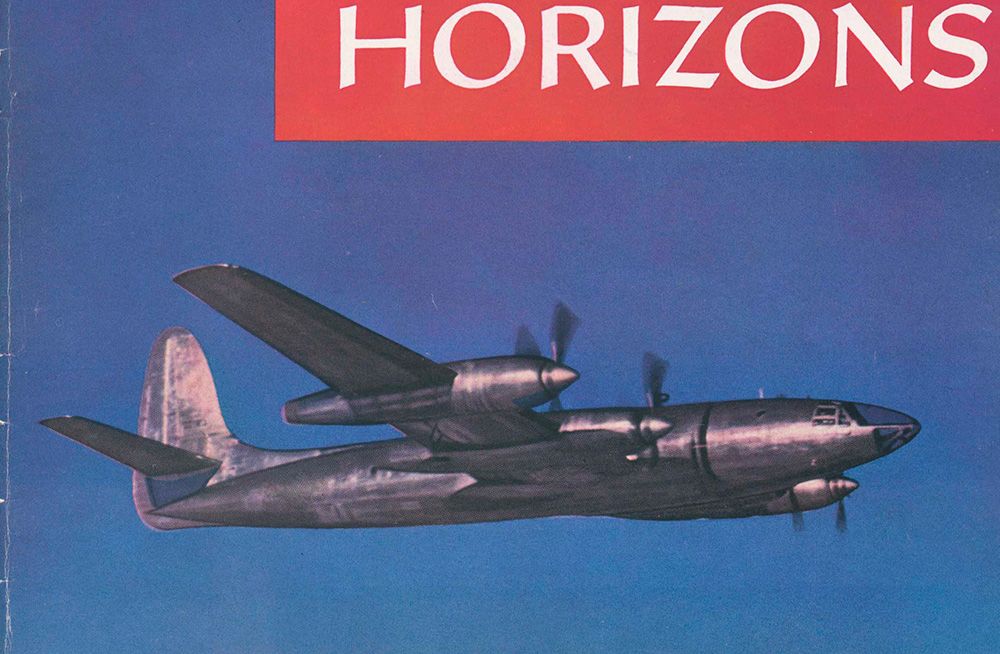

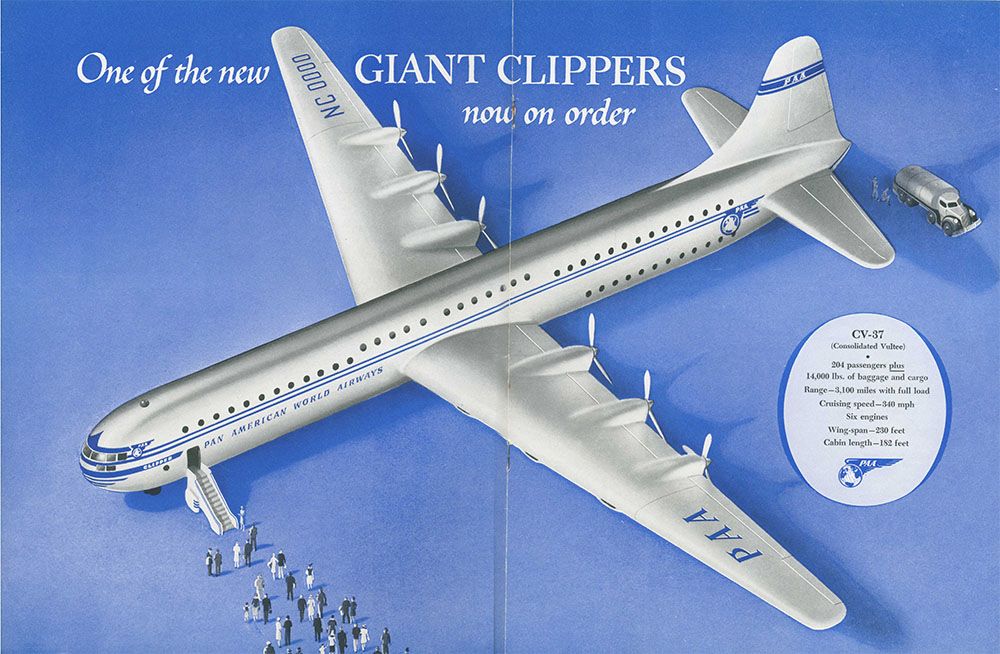

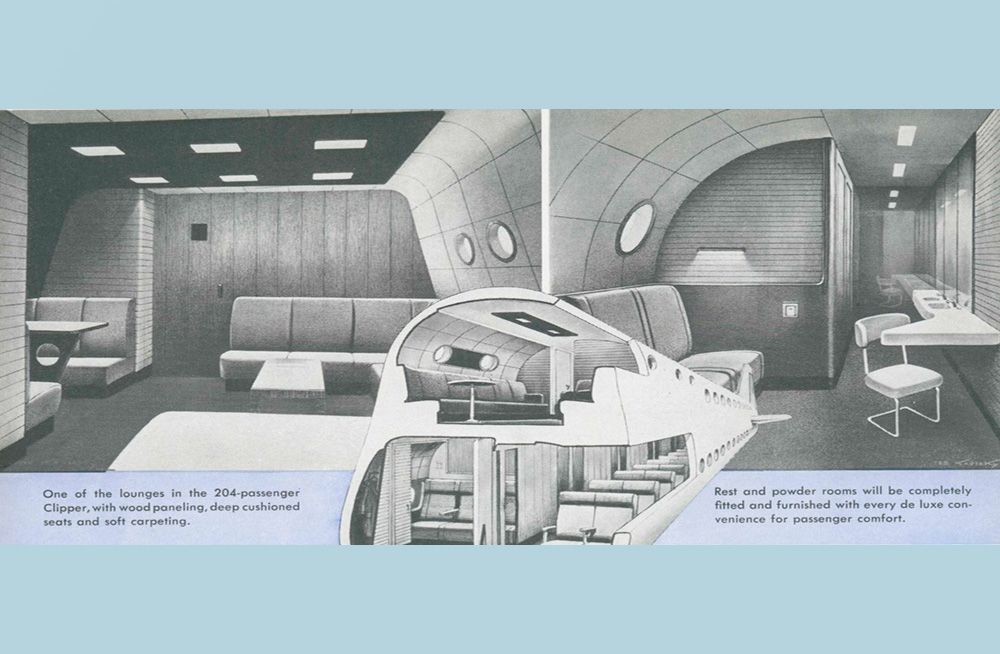

Beyond that, futuristic Clippers might include the Republic Rainbow and the CV-37, a civilian version of what would become the massive Convair B-36 bomber

It seemed as if the war was only a temporary setback. Juan Trippe explained to stockholders that the flying boats had been planned for retirement in 1942 or '43, but like so many plans, the war had got in the way.

FUTURISTIC LAND PLANES

Republic Rainbow concept (Courtesy Aeroart International).

Republic Rainbow prototype (Courtesy Aeroart International).

CV-37 Exterior concept (Courtesy Aeroart International).

CV-37 Interior concept (Courtesy Aeroart International).

Pan American Airways ad, 1946. If it isn't operated by Pan American it isn't a Clipper (Duke University, J. Walter Thompson archive).

Pan American Airways ad, 1946. If it isn't operated by Pan American it isn't a Clipper (Duke University, J. Walter Thompson archive).

PISTONS AT THEIR PEAK

Technology had taken leaps and bounds. Substantially more powerful piston engines were available now, like the Pratt and Whitney "Wasp Major," "Double Wasp" and the Wright R-3350. Large engines like these making possible the generation of commercial aircraft that would be carrying passengers twice as fast, and more than twice as high as the old flying boats, above most of the weather, and would reach the far shore of the Atlantic in half the time, or less.

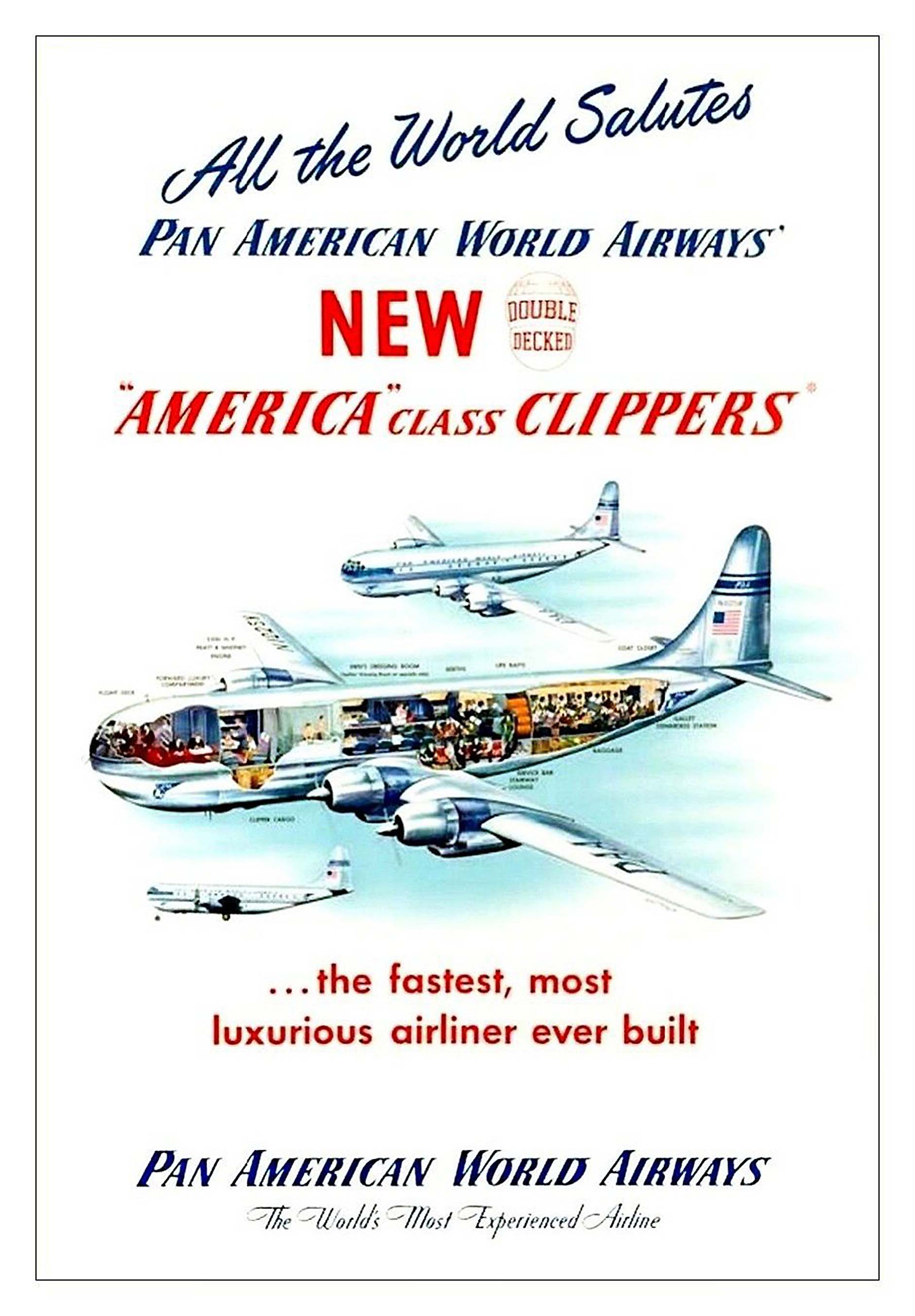

Pan Am B-377 Stratocruiser, 1949 ad (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

Pan Am B-377 Stratocruiser, 1949 ad (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

All the world salutes Pan American World Airways' new double decked "America" class Clippers ...the fastest,most luxurious airliner ever built

And beyond that vision, there was the promise of jet engines

First put to practical use by the German Luftwaffe in the war, it was obvious to serious observers — like Juan Trippe — that these new engines could change the face of aviation. But there was a lot of work to do before that day would come.

Pan Am's business was different now as well. Before the war, the airline was the only game in town as far as US international air travel. With war's end, the gates were opened to transatlantic competition, such as TWA and American Overseas Airlines. The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) seemed bent on dismantling Pan Am's prewar monopoly on foreign air routes.

Non-scheduled airlines such as Transocean were also nibbling at Pan Am's heels, gaining charter contracts that might otherwise have gone to Pan American.

Trans World Airlines Lockheed Constellation, photo by Jon Proctor, Phoenix Sky Harbor, July 1960 (Wikimedia Commons).

Trans World Airlines Lockheed Constellation, photo by Jon Proctor, Phoenix Sky Harbor, July 1960 (Wikimedia Commons).

A DIFFERENT WORLD

The aviation world that emerged from WWII included new international organizations. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) was part of the new United Nations, and helped regularize nuts and bolts information sharing, such as airport codes and communication protocols.

ICAO/OACI logo, c. 1960s (University of Miami Special Collections).

ICAO/OACI logo, c. 1960s (University of Miami Special Collections).

Another organization had a more direct impact on Pan Am after the war. This was IATA (International Air Transport Association) had started in Europe, and admitted Pan Am in 1939 when the Clippers arrived in Europe. International civil aviation was in disarray to some extent. Coordination was desirable, if not essential for a workable international system. IATA acted as arbiter to coordinate fares and schedules.

IATA logo, c. 1960s.

IATA logo, c. 1960s.

With peace, European airlines were eager to fly to the US, but wanted to maintain a stable price and schedule structure to minimize competition.

Before its flight...all seats on "The Rainbow" were sold out for three months! (Duke University, J. Walter Thompson collection).

Before its flight...all seats on "The Rainbow" were sold out for three months! (Duke University, J. Walter Thompson collection).

Juan Trippe saw the situation differently, and pushed for a low "tourist" fare. For a long time, IATA balked, but eventually agreed. As in so much else in the evolution of modern air travel, Juan Trippe's understanding of the core value proposition of air travel proved to be irresistible.

The acceptance of air travel was gaining rapidly after the war, and an expanding middle class, on both sides of the Atlantic, spurred on by increasing access and use of credit, was finding that international travel by air could fit into their lifestyle.

By the start of the 1950s, Pan Am's US competitors, TWA in particular, had a strong domestic route network that fed passenger traffic directly to its transatlantic flights.

European airlines like BOAC, KLM, Air France, and Sabena, received government subsidies. Pan Am had to survive with what it could earn.

The keys to success, as Trippe, saw was three-fold: market growth, passenger service, and increasing efficiencies of scale. Pan Am strove to keep the cost of flights affordable in the face of resistance from IATA's cartel-like resistance.

VIDEO

Footage: Traveling to Europe on a Pan Am Boeing 377 Stratocruiser was a luxurious experience (Pan Am Historical Foundation).

The eventual acceptance of "tourist class" fares by IATA in 1952 was a significant victory for Pan Am. And the airline worked consistently on its marketing, making liberal use of motion pictures to entice new customers onto Clippers. And in those films, the excellent quality of passenger experience was front and center. Another selling point was Pan Am's impressive route structure, particularly in Europe, where most American's would be headed. Pan Am's marketing was tuned to some demographic nuances, often targeting specific groups.

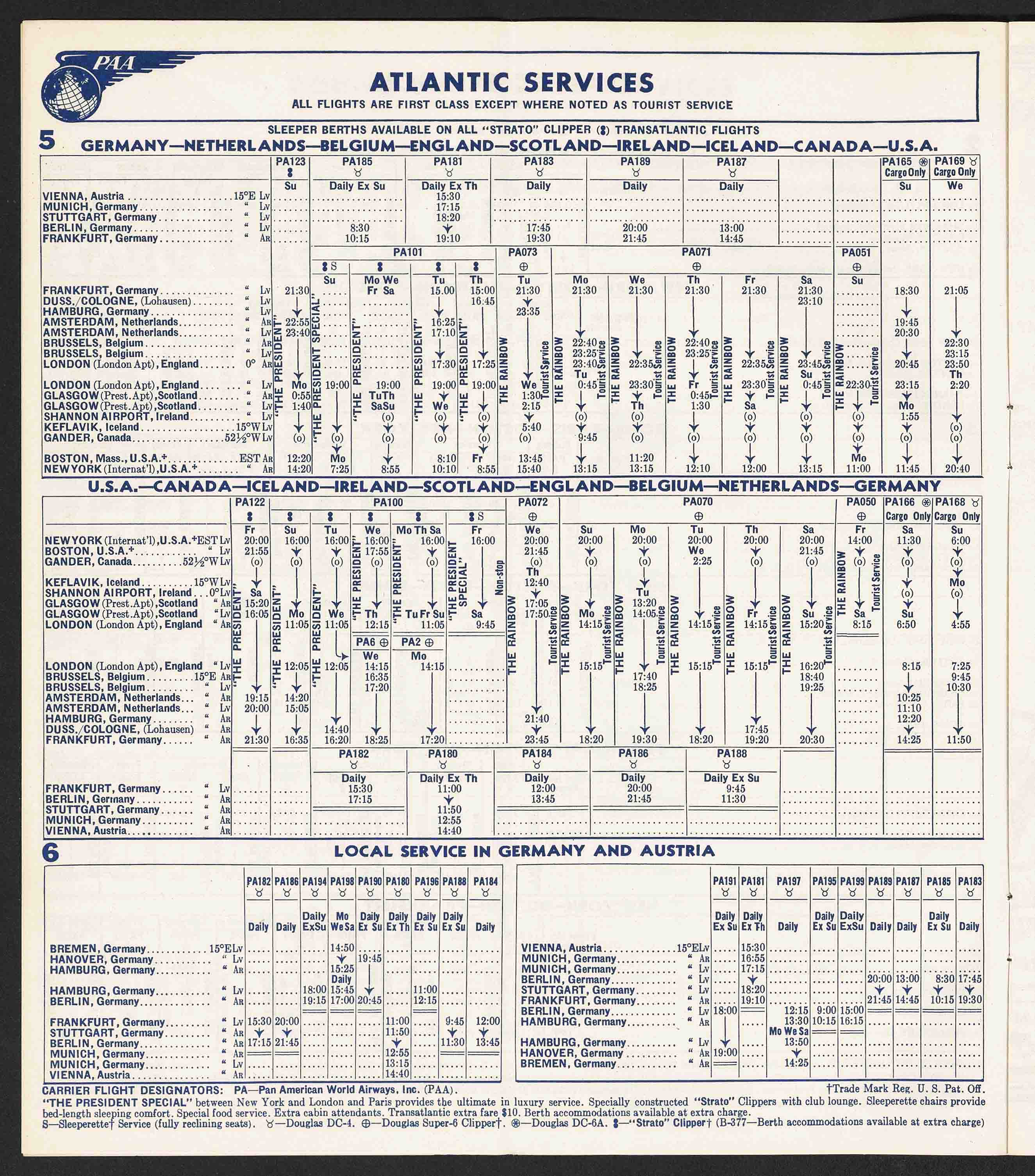

Atlantic Services Time Table, December 1, 1952 showing destinations around Europe (University of Miami Special Collections).

Atlantic Services Time Table, December 1, 1952 showing destinations around Europe (University of Miami Special Collections).

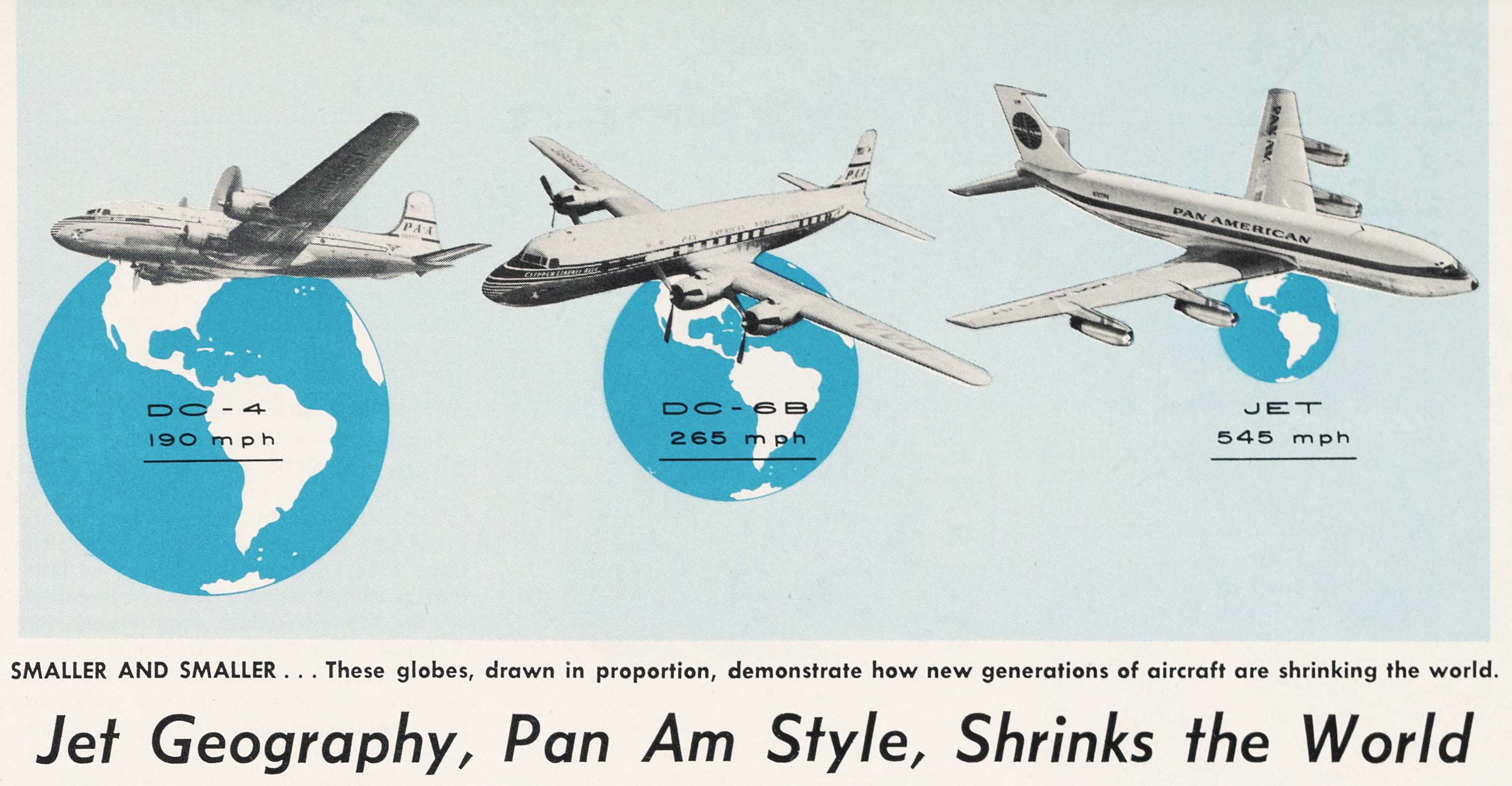

As far as efficiencies of scale, Trippe was focused laser-like on seat-mile cost. He understood perfectly how the business of Pan American boiled down to an equation of getting the most people in the most airplane seats at the least cost. And in that equation, the higher the utilization of an airplane, the lower the cost. In practice that meant bigger planes making faster trips. This equation was particularly applicable to the transatlantic market.

Now — Big Reductions in Fares, from December 1, 1952 Atlantic Division Time Table (University of Miami Special Collections, Pan American World Airways, Inc records).

Now — Big Reductions in Fares, from December 1, 1952 Atlantic Division Time Table (University of Miami Special Collections, Pan American World Airways, Inc records).

MARKET GROWTH & NEW POTENTIAL

Hotel Intercontinental Geneve: "The façade had a classical feel that was enlivened by the checkerboard pattern formed by the opened or closed position of the windows’ curtains. Ariana Park and the Palace of Nations, the former headquarters of the League of Nations that became the home to the United Nations Geneva in 1946, was within walking distance" (New York School of Interior Design Library).

INTERCONTINENTAL HOTELS

The same vision that supported a wider market for air travel was complemented with the start of the Intercontinental Hotel Corporation. With the help of a $25 million dollar credit from the US government, Pan Am invested $50 million to build its first hotel in Bogota just after the war. By the end of that decade, the chain had expanded to Brazil, and soon after, the Caribbean. By 1963, hotels had been opened in Europe, in time to benefit for the travel boom of the 1960s. As Pan Am increased transatlantic flights, it drove more business to InterContinental properties. The hotels were strategically located in cities served by Pan Am, allowing for seamless travel experiences and Intercontinental expanded its hotel network as Pan Am added new transatlantic destinations, offering quality accommodations.

IHG Hotels and Resorts History

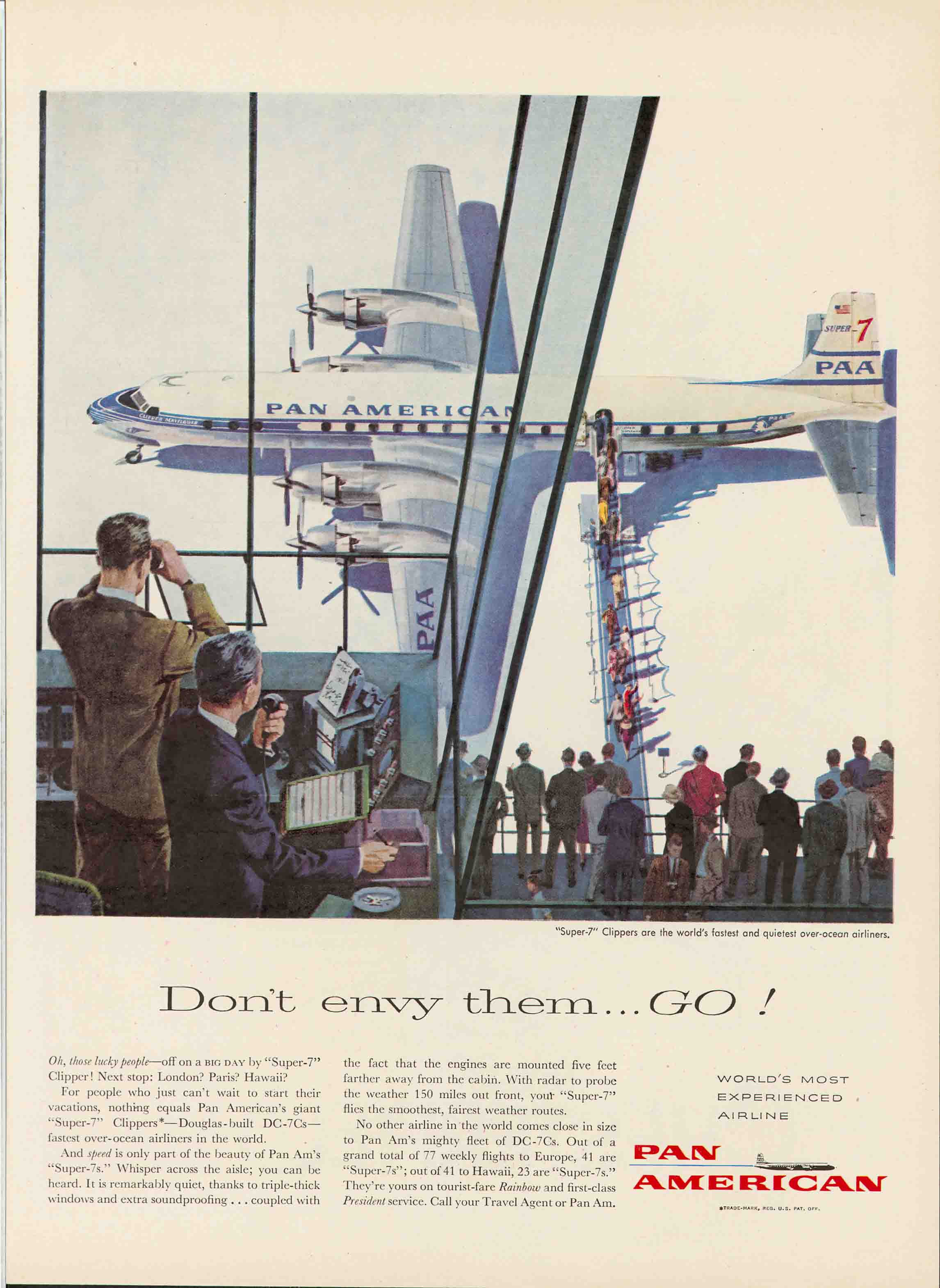

1957 Don't Envy them... Go! featuring a DC-7C Super 7 (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

1957 Don't Envy them... Go! featuring a DC-7C Super 7 (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

With the closing years of the 1950s, the coming changes were becoming palpable in all sorts of ways. Juan Trippe's paradigm-shifting 1955 decision to move beyond piston-engined airplanes in favor of jet-powered transports played a big part. There already were signs that a new globally-connected world was in the offing, where travel distances and time would be even further diminished. By 1957, Pan Am DC-7Cs had the range to fly transpolar routes from US West Coast cities to Europe. Adapting this "Great Circle" route reflected one of Trippe's most consistent ambitions. On Atlantic crossings, the same DC-7C's were now able to skip westbound refueling stops in Newfoundland that had been standard practice since the beginning of North Atlantic flights in the '30s.

A SID STIBER PRODUCTION

Pan American Airways production: Transatlantic Anniversary, c. 1957 (Pan Am Historical Foundation Collection).

JET SET CULTURE

Image from Pan Am Sales Clipper, Vol 18, No. 2, February 1960, p. 5 (University of Miami Special Collections, Pan American World Airways Inc. records).

Image from Pan Am Sales Clipper, Vol 18, No. 2, February 1960, p. 5 (University of Miami Special Collections, Pan American World Airways Inc. records).

The first foray into using jets as civil transports was taken by BOAC, which started operating DeHavilland Comet I jets in 1952. But a series of catastrophic crashes grounded the fleet, and it was several years before the British were ready to try again with a completely revamped design.

In the meanwhile, American plane manufacturers were busy turning out military jets. Boeing in particular was doing well, and had developed a large four-engine jet to be used for aerial refueling.

This plane had the potential for civilian use, but it would take prodding from an outside source - Juan Trippe - to get that going. Trippe was working on Pratt and Whitney to release a new generation of jet engines, also meant for military use. In the end, Trippe got what he wanted, and was ready to commit to a massive purchase of 45 jet aircraft - 20 from Boeing, and 25 from Douglas. He announced this, in his offhand manner, at a meeting of European airline leaders in October 1955. The news was stunning, and the train of events set in motion.

1955 First jet transocean service! First jet transcontinental service! Boeing Jet Stratoliner (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

1955 First jet transocean service! First jet transcontinental service! Boeing Jet Stratoliner (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

In 1958, Pan Am introduced the Boeing 707-121. The transatlantic flight from New York to Paris on October 26 marked a divide in the history of transportation as significant as the introduction of steam powered ships. The initial Boeing model was soon followed by longer-ranged successor variants. Before long, the concept of the "jet set" creeped into common use. By definition "jet setters" were going places at close to super-sonic speeds, unfettered by convention, sophisticated, and worldly.

1958 New on Pan Am - Daily Service to Europe by Jet Clipper (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

1958 New on Pan Am - Daily Service to Europe by Jet Clipper (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

Pan Am's new icon - the "blue ball," adopted in 1957 - matched the jet age thrust into the future. Now the airline's advertising, and new approaches to fare and travel arrangements were capturing an expanding market. Americans and Europeans alike were perceiving the world was more accessible than it used to seem.

Movie goers saw glamorous, exciting scenes of far-away places, much of it involving transatlantic travel - often as not via Pan American aircraft playing a part. It wasn't a surprise that James Bond - British secret agent 007 - would be seen flying Pan Am.

CULMINATION OF A DREAM

THE 747 JUMBO

VIDEO

"The Jumbo Era, "The First Transatlantic Boeing 747 - Pan Am (Movietone News) AP.

THE BOEING 747

Perhaps it was an inevitable result of the success of the '60s, but by the middle of the decade predictions for airline travel growth alarmed planners at airlines and airports alike. The generation of jet transports that could carry over 150 passengers was proving inadequate to accommodate business. The answer was not more of the same. Transatlantic traffic alone was clogging airports on either side of the ocean, and the air traffic over it was maxing out air traffic capabilities.

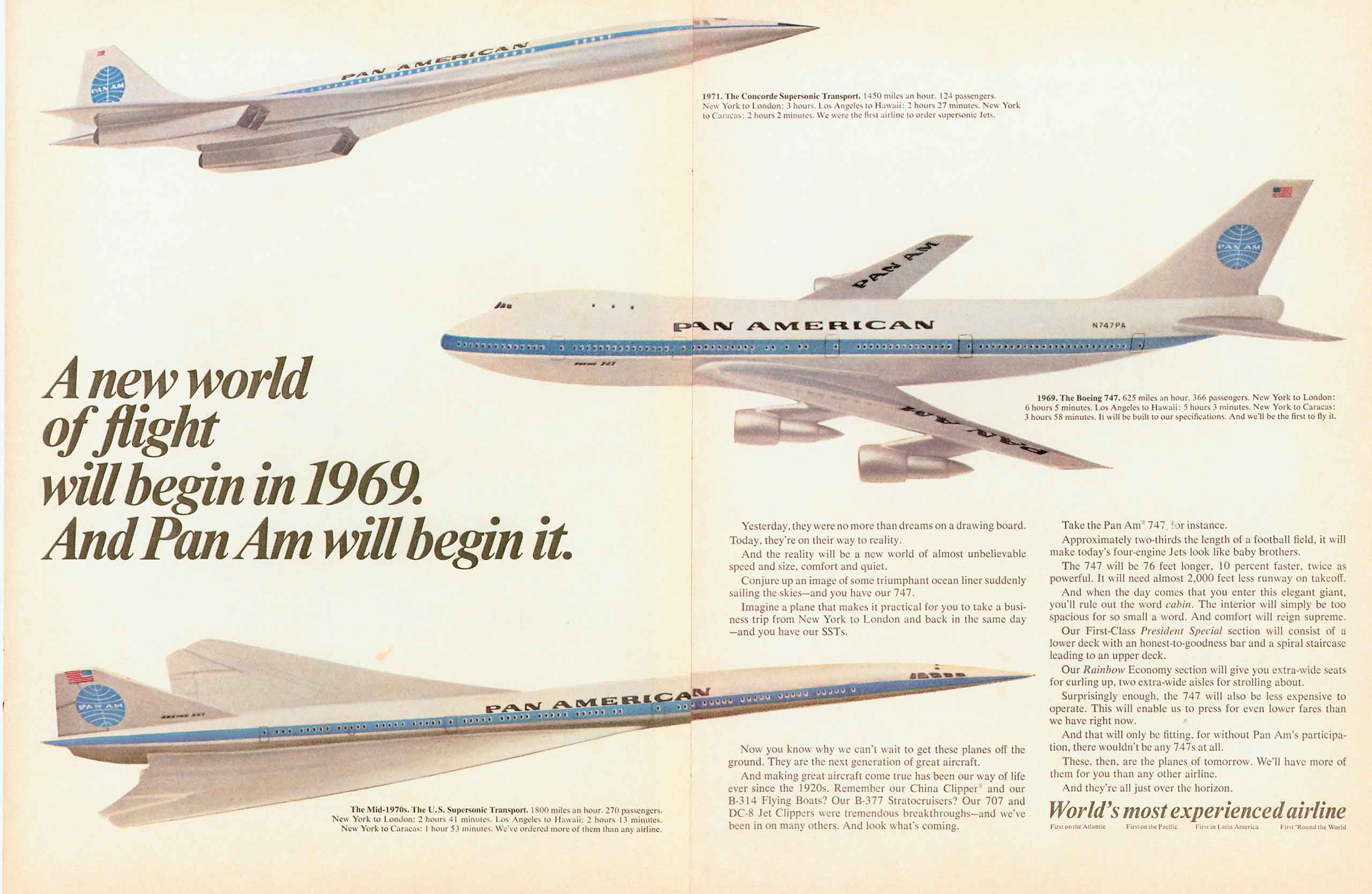

A new world of flight will begin in 1969. And Pan Am will begin it. (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

A new world of flight will begin in 1969. And Pan Am will begin it. (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

The answer was not more of the same. The future lay in bigger aircraft. As always, the vision to see this eventuality was that of Juan Trippe. He knew that it was time to prod the aircraft manufacturing sector into providing the solution.

The US Air Force had sought to obtain a new military transport with massive airlift capabilities, to be called the C-5. Lockheed had won the bid, but it was not the right fit for conversion into civilian use. Boeing had also bid on the contract, but their design was turned down. Trippe thought the Boeing design might be adapted to his requirements, and he went to work on his old friend Bill Allen, President of Boeing.

Boeing 747-100 illustration by Mike Machat from Pan Am, An Airline and It's Aircraft by R.E.G. Davies (From Jamie Baldwin's JPBTransconsulting.com website).

The legend has it that their conversation went something like: "If you buy it, I'll build it." To which Trippe responded "If you build it, I'll buy it!" However it happened, the deal was done in 1965, and soon one of the most massive industrial projects undertaken to that point got underway.

The almost incredible size and speed of the B-747 program is a story best told elsewhere, but it meant a massive commitment for both Boeing and Pan American. It was Juan Trippe's crowning achievement as an airline empire builder, and when he stepped down from Pan Am's leadership in May, 1968, he must have felt that he had achieved the realization of an almost life-long ambition that stretched back to his days as a young college student and Navy pilot.

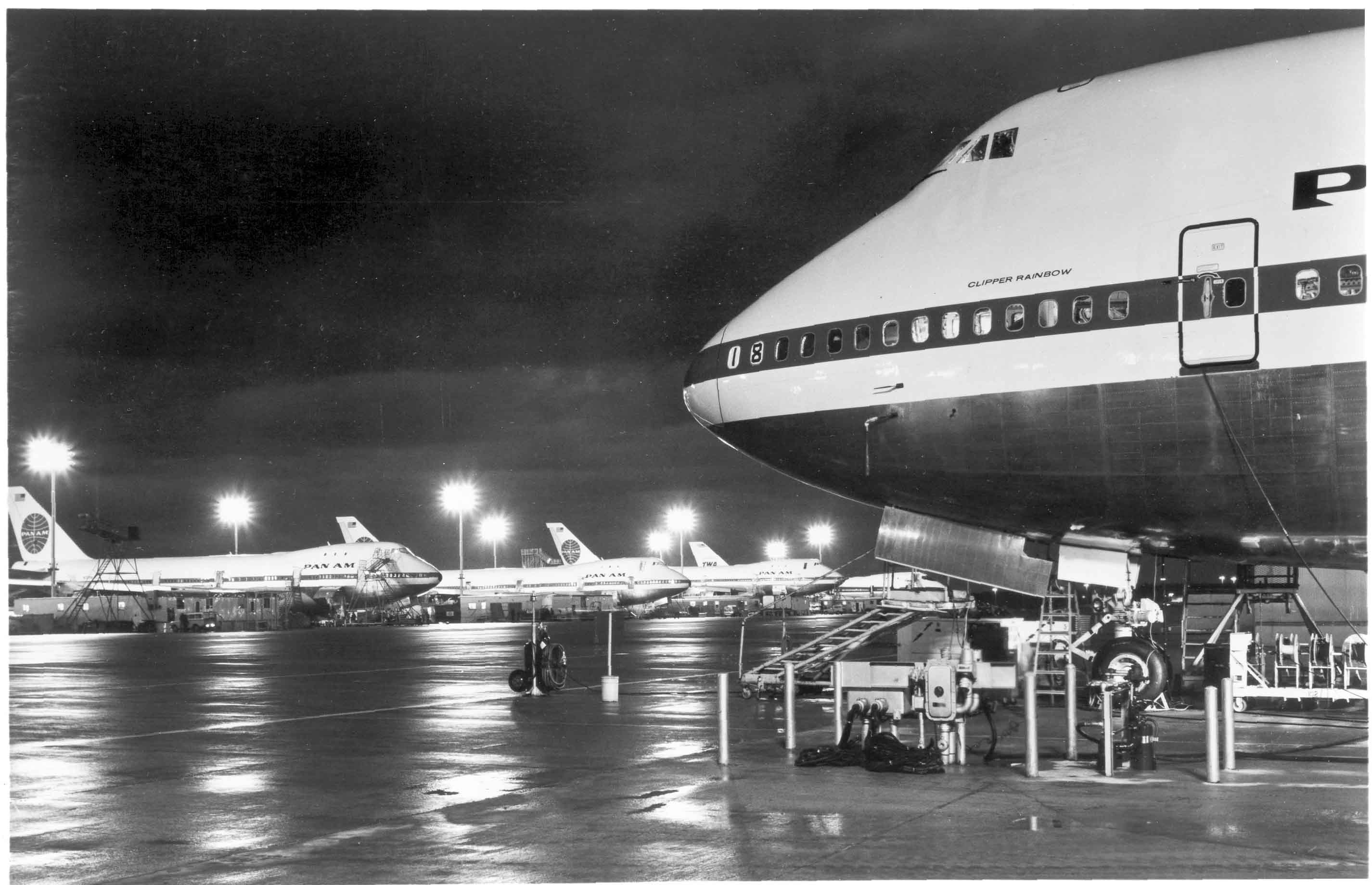

Pan Am Boeing 747-121 line up at the Boeing Factory (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

Pan Am Boeing 747-121 line up at the Boeing Factory (Pan Am Historical Foundation collection).

The new plane, when it first flew with paying passengers in January 1970 — for Pan Am, the launch customer — made an Atlantic crossing. As it had been a half-century before, the transatlantic connection remained the world's premier air route. Pan American's cachet and reputation as the world's most significant international air carrier was only burnished more brightly by being the first across the Atlantic with this game-changing new airplane.

1919-1969

A HALF CENTURY OF ATLANTIC CROSSINGS

Even before there was a Pan Am, Juan Trippe's vision was focused on crossing the Atlantic Ocean. And over the course of a half-century, it was where aviation's future was forged. Juan Trippe was the master builder, with Pan Am his instrument.

No matter what lies ahead for commercial aviation, the paths taken to bring the two shores of the Atlantic closer by air have proved to be the foundation of aviation's future.

Group of United States Aviation Industry Pioneers at a Boeing Dash 80 event. (Right to left) Juan Trippe of Pan Am / with CR Smith, American / Bill Allen, Boeing / William "Pat Patterson" of United / Charles H. Dolson, Delta / Eddie Rickenbacker, Eastern, c. early 1970s.

Group of United States Aviation Industry Pioneers at a Boeing Dash 80 event. (Right to left) Juan Trippe of Pan Am / with CR Smith, American / Bill Allen, Boeing / William "Pat Patterson" of United / Charles H. Dolson, Delta / Eddie Rickenbacker, Eastern, c. early 1970s.

VIDEO: "THEY HAD GREAT THINGS TO SAY!"

The end results of decades of evolving transatlantic efforts are obvious when you hear what these British passengers have to say about Pan Am, c. 1980s.